Wednesday, December 1, 2010

All problems can be solved musically--Dean Young

"All problems can be solved musically. On one of those umpteen Miles Davis box sets, there are three takes of a single song: in the first Coltrane hits an obviously off note, a clam it’s called in the recording industry, in the second he hits it again, at a different point, augments it, chooses it, this is Coltrane, man, so by the third time it’s not a wrong note, it’s an integral part of his solo . . . Life my friends is a mess. Mistakes aren’t contaminants any more than conception is infection. Fucked up before I got here, fucked up while I hung around, fucked up when I’m gone. Good news!" (154)

Monday, November 8, 2010

Second Installment--Musical Ekphrasis

I want to pick up on a number of things tonight, trying to address a few of the questions and concerns folks raised. First, let me remind you of the several kinds of musical ekphrasis I identified, only the first of which I posted on. I wrote:

I see modern/contemporary poets responding to music in these four or five ways:

1) memorial/commemorative (music as invocation of particular individual experiences)

2) contextual icon (poems exploring music as cultural/biographical/historical means into a composer’s life, an era, etc.)

3) mimetic/echoing (poems that imitate and seek the physical/sonic/emotional effects of music)

4) music as figure/god/form (poems that identify music as an idealized form of making art/meaning or as a version of mystery/power beyond language)

5) the riff (music that improvises and dialogues with music, drawing together many or most of the notions above in a single place)

So my mentor for the semester said this in response to my post:

I've always equated ekphrasis with writing about a particular painting or drawing or photo. I'm thinking about William Carlos William's "Landscape with the Fall of Icarus." So I was surprised that these poems all seemed to be about a personal experience that the speakers had with music: the mother playing the piano, the kid singing to the juke boxetc. They weren't responses to music so much as memories of events and people connected to music. Would you agree?

Here's how I would/did respond:

Absolutely I agree.* In these poems music is a springboard, often even particular pieces of music or particular singers/composers/etc. for the epiphanic, memorial lyric. At one point I was going to write something like this to talk about how such poems, as much as I love them, often ignore the actual experience of music:

At my age, nearly every one I know has a dead grandma with a favorite hymn. Or an involuntary moment of sexual arousal upon hearing the first five notes of an album he made out to in high school. Or can still sit down at the piano or pick up a guitar and play the first song she learned. Or sustains a perverse love for a marginal pop hit to which we made up alternative/obscene lyrics to be sung in the car (lyrics which have since completely erased all memory of the original words). And almost every poet I know (these are quite often the very same people) has a set of poems about the hymn to which his dead grandma made out in high school while her boyfriend played the guitar and made up alternate lyrics.

But of course I realize that for most of us memory and music are so inextricable (see this amazing study) that it would be impossible to shut off poems about music from such associative connections. And why would you want to, completely?

Still, I find these poems limited precisely because there is so, so much about music they really do not take into account, so let me skip number two in my list and move on to number three:

3) mimetic/echoing (poems that imitate and seek the physical/sonic/emotional effects of music)

Of course I have a long, long discourse on this in my essay, but I want to point out just two poems.

First, Langston Hughes, who was one of the first to attempt to tranlate the experience of the blues (the music, not the emotion) into modern poetry. What some scholars have noted about this process, is how Hughes’ attempts developed over time from, at first simply transcribing or mimicking blues lyrics and rhythms. But readers/scholars almost universally agree “[t]hat Hughes writes his best blues poetry when he tries least to imitate the folk blues is a critical commonplace” (Chinitz 179). While David Chinitz (one of my former profs at Loyola University in Chicago) challenges this common wisdom, I still the basic insight it instructive. The musical ekphrastic poem is an engagement with the music.  Rather than a mere transcription of the blues, or an attempt to write lyrics to be sung, blues poetry follows Langston Hughes' struggle to capture "the quality of genuine blues in performance while remaining effective as poems" (Chinitz 177). For Hughes and the many writers who merge into and out of the tradition (see some attached suggestions below) the central challenges have been "First, how to write blues poems in such a way the they work on the printed page, and second, how to exploit the blues form poetically without losing all sense of authenticity" (177).

Rather than a mere transcription of the blues, or an attempt to write lyrics to be sung, blues poetry follows Langston Hughes' struggle to capture "the quality of genuine blues in performance while remaining effective as poems" (Chinitz 177). For Hughes and the many writers who merge into and out of the tradition (see some attached suggestions below) the central challenges have been "First, how to write blues poems in such a way the they work on the printed page, and second, how to exploit the blues form poetically without losing all sense of authenticity" (177).

So to see how Hughes works through/past that challenge, we can take a look at his most famous blues poem, The Weary Blues and see how he combines several impulses to generate a kind of musical experience that adds to or supplements the blues. He gives us a narrative and a character that frames the several quotations from an actual blues tune. The rhyme, repeated lines, and quotations combine to feel like the blues, even though they are not all strictly blues forms. But then other poetic devices, like alliteration, assonance, caesuras also do things poetry can do that an actual blues singer cannot.

So as you write, or try to write a poem about music, what poetic tools can you bring to the poem that do something in addition to describing or transcribing a musical encounter?

Second, some poets adopt new formalist techniques to give a musical texture to their poems, reaching back into the deeper connections between music and poetry. A. E. Stallings has done this often, most notably I think in Blackbird Etude where her small stanzas (rhymed haikus with their 5, 7, 5 syllabics), her enjambed rhyme, and her sonic play with unexpected diction (“melismatic runs sur-/passing earthbound skills”) give music-like shape to the blackbird’s song. She shapes a wild creatures song with poetic forms and reference in the title to an etude, that most classical sort of music pedagogy.

Myself, I love the pantoum as a musical form, one that allows me to make music while at the same time not merely imitating (I hope). Here’s a pantoum from a number of years back responding to a performance by Ella Fitzgerald near the end of her life, an experience at the time I had no idea was so remarkable.

If you want to try and write a musical poem, two considerations I would make. What is the form of the piece of music, at least as you understand it. Can you use that as at least a shape to your poem? For instance, a poem about a sonata might be a four or five part poem, loosely following the music form. Even though you cannot reproduce the exact tones, rhythms, etc. of the sonata, you could rely on its shape to “inform” your own poem.

Second, I always try to think not just of the music’s formal qualities, but also the form of my experience of the music. For instance, Hughes' narrative and cultural explorations in "The Weary Blues" are central to the poem. Or in my Ella poem, I am thinking of how my mind wandered from her frailty to the qualities of the music, to the associations I have with other jazz musicians when I think of her, to the connotative possiblities of words like "trip."

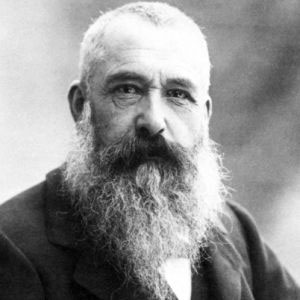

*Though I would work with a more expansive definition of ekphrasis than those poems that  write about only a single work of art. I think one of the best, and an example of visual ekphrasis that falls into my second category above, is Lisel Mueller's Monet Refuses the Operation which refers to a whole list of Monet’s works, using the painter’s voice to describe and examine them (and lift them off the page).

write about only a single work of art. I think one of the best, and an example of visual ekphrasis that falls into my second category above, is Lisel Mueller's Monet Refuses the Operation which refers to a whole list of Monet’s works, using the painter’s voice to describe and examine them (and lift them off the page).

Here's the formal bib reference to David Chinitz's article:

Literacy and Authenticity: the Blues Poems of Langston Hughes." Callaloo 19 (1996): 177-92.

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Four Anthologies of Musical Ekphrasis

Music Lover's Poetry Anthology, ed. by Helen Hardy Houghton and Maureen McCarthy Draper

Music's Spell: Poems about Music and Musicians, ed. by Emily Fragos

Jazz Poems, ed. by Kevin Young

Blues Poems, ed. by Kevin Young

Monday, November 1, 2010

Discussion One on Musical Ekphrasis

“Writing about music,” says Elvis Costello (or Steve Martin, Thelonius Monk, Laurie Anderson, Martin Mull, Frank Zappa, etc.) “is like dancing about architecture. It’s a stupid thing to want to do.” This hasn’t stopped me (or most of the poets I regularly read) from writing dozens of poems about music—music as source of inspiration, font of memory, ideal of form, or subject of artistic envy. Then again, I am also someone who was once spotted dancing on a hill near a Frank Lloyd Wright hotel in southwestern Wisconsin)

My essay explores the dynamics of “musical ekphrasis.” If you want a formal preview, you can read the abstract, or you can refer to the “map” of the essay above.

Here, though, is some material for us to discuss on how poets write in response to music and musical experience.

First a few caveats, definitions, and misdirections:

1) What I am NOT writing about—the shared lineage of music and poetry (I too believe that all the ancient poets were bards who sang their epics and their lyrics on honeyed tongues to the listening masses—but that’s not what I am studying—and besides that hasn’t been the case for say, oh, about a thousand years). Also, I’m not writing about whether or not lyrics (popular or otherwise) qualify as poetry (a subject on which I have many strong, well-informed opinions, none of which matter in this essay—short answer, “usually not”). Also, though I am interested in the notion, I am not writing about how musicians respond to works of visual art (which is what this scholar has done).

3) Though ekphrasis has its origins in ancient Greek rhetoric, I’m talking here primarily about the poetic tradition that picked up steam in the early 19th century with work by the Romantics who frequently depicted encounters with visual art as nearly sacramental (in ways often replacing more formal religious encounters and challenged only by direct encounters with nature). Of course the great example of this is John Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn." And then there are countless 20th century examples of ekphrasis, the modernists Stevens, Williams, Stein, Auden and since.

4) Of course you can read Keats’ “Ode” as not only an essential/founding example of ekphrasis but also as an emblematic poem of musical ekphrasis—the relationship between silence, music, imagination, and poetry. Melodies, pipes, timbrels, song occupy nearly as much space in the poem as anything else. And so I want to make a case that musical ekphrasis can be seen as an equally important category of poetry, especially in modern and contemporary poetry.

5) In truth, though, I don’t really want to “make a case” for anything (that’s why I gave up on my dissertation and turned to making my own poems instead). I would rather explore HOW poets respond poetically to music and suggest how this has been valuable to my own reading, writing and teaching of poetry and how it might prove valuable and generative to the work of other writers and readers. I’m also interested in this with visual ekphrasis, which explains why I have taught courses in both subjects and used to keep an ongoing blog on the subject. Plus, Lauren Rusk already wrote a very strong piece for the AWP Chronicle a few years back on “The Perils and Possibilities of Writing about Visual Art.” At the end of the week, I will put up a prompt, some suggestions, and some warnings for writing musical ekphrasis, stuff I hope you all might find generative of new work.

MUSICAL EKPHRASIS

The contemporary practice (1920s through yesterday) of musical ekphrasis takes on a thousand varieties of form and approaches, but at the core I am interested in those poems that struggle to improvise a space that is itself an experience (in and through language) of a felt knowledge, a resonant intimacy, and an embodied/shared sonic experience generated primarily by an encounter with music.

I see modern/contemporary poets responding to music in these four or five ways:

1) memorial/commemorative (music as invocation of particular individual experiences)

2) contextual icon (poems exploring music as cultural/biographical/historical means into a composer’s life, an era, etc.)

3) mimetic/echoing (poems that imitate and seek the physical/sonic/emotional effects of music)

4) music as figure/god/form (poems that identify music as an idealized form of making art/meaning or as a version of mystery/power beyond language)

5) the riff (poetry that improvises and dialogues with music, drawing together many or most of the notions above in a single place)

So each day this week, I am going to put forward a poem or two that stand inside one of these categories and ask for your response.

Memorial/Commemorative Musical Ekphrasis

Here are a number of poems that attempt to give “an account of an unforgettable moment” that is tied directly to music, to show “how music has shown us to ourselves more accurately, and given us as well the eerie means to understand transcendence—to step back out of our lives and look back at them” (McClatchy xv).

If you would, pick one of the poems and discuss how it marries/connects music with memory.

How does the poem celebrate, lament, question, reject the musical experience?

And what craft choices does the writer use to represent the music itself?

Which piece of music in your experience immediately evokes powerful memories for you? Have you written about this piece?

Or, alternately, do you have a suggestion of a poem that connects music and memory? I’d love to see it.

Edna St. Vincent Millay, “On Hearing a Symphony of Beethoven”

Frank O'Hara "The Day Lady Died" (Here is Billie Holiday singing "God Bless the Child")

Linda Pastan, “Practicing”

Dorianne Laux, "The Ebony Chickering"Denis Johnson, “Heat”

Wendell Berry, “A Music”

Naomi Shihab Nye, “Hugging the Jukebox”

Kevin Stein, “First Performance of the Rock ‘n’ Roll Band Puce Exit”

Abstract of an Essay in Progress

As part of a graduate MFA course, I am trying to tame a paper on Musical Ekphrasis. Above is what it looks like when I work on such things. Here is the abstract of the essay.

Ekphrasis--the practice of writing poems in response to visual art--occupies a prominent place in modern and contemporary American poetry (though it dates back centuries, gaining special esteem during the era of Romanticism). Drawing on this deep ekphrastic tradition, this essay proposes "musical ekphrasis" as an equally valuable way to consider and generate contemporary poems. Musical ekphrastics are poems that represent, respond to, and engage sensuously with musical experience. Langston Hughes, Frank O'Hara, Lisel Mueller, Jean Janzen, Terrance Hayes, and others write poems that grow from various encounters with music, often experimenting with formal innovation and deeply embodied imagery. The poets engage musical experience in memorial, figurative, contextualized, lyrical ways that can be understood as relating to ekphrasis. However, the poems also have their own unique mean of poetic knowing, a way best understood in terms of improvisation between writers, musicians and readers. Practical considerations for how poets might attend to music in a generative fashion conclude the essay.