Tuesday, December 25, 2007

Monday, December 24, 2007

Sunday, December 16, 2007

Painting by Chagall-The Weepies

Painting by Chagall--The Weepies

Thunder rumbles in the distance, a quiet intensity

I am willful, your insistence is tugging at the best of me

You're the moon, I'm the water

You're Mars, calling up Neptune's daughter

Sometimes rain that's needed falls

We float like two lovers in a painting by Chagall

All around is sky and blue town

Holding these flowers for a wedding gown

We live so high above the ground, satellites surround us.

I am humbled in this city

There seems to be an endless sea of people like us

Wakeful dreamers, I pass them on the sunlit streets

In our rooms filled with laughter

We make hope from every small disaster

Everybody says "you can't, you can't, you can't, don't try."

Still everybody says that if they had the chance they'd fly like we do.

Monday, December 10, 2007

ENGW 333/Fall 2007--Poetry Critique Guide

Print and read each poem scheduled for your group critique session, marking any passages or concerns that strike you as you read. Then take no more than 15 minutes to respond to the questions below, giving as specific a response as you can. You will give your responses to the poet, so make comments legible (type if you can) and references to the manuscript specific (stanza numbers, particular lines, etc.).

Reader Response(s)

1) As you finish the piece, record your initial response as a reader. Are you jealous? Overwhelmed? Confused? Thrilled? Eager to read more? Calmed? Reminded of something? What in the poem or poems most powerfully contributed to this response?

2) What conversations do you overhear as you read this work? Which voices (the poet’s, the artist’s, the audience’s, or other voices) most attracted you? Which ones compelled you to learn more in order to read the poem better? Which voices kicked you out of the poem?

3) What role does the artwork or song play in this ekphrastic piece? Is it central or peripheral? In what ways would you like to understand the work more fully—through the artist, through description, through reception, through context?

4) What role does the speaker or poet play in this ekphrastic poem? Where would you like to experience more distance between the speaker and the work? Where would you like to see the poet better collapse such a distance? How might he or she do this? How might your sense of this distance change as you encounter more poems in the grouping?

Formal/Technical Concerns

1) How does the writer’s choice of form fit or fail to fit with her artistic subject matter? What aspect of the form is he using with special skill? What aspect of the form could still be brought to bear on the poem? (For instance, perhaps the voice in a dramatic monologue is strong, but the writer hasn’t made use of the implied audience).

2) Which images in the poem are especially strong? Which sense does the writer use best? Which sense could he or she develop more here? Where would you like to see a particular image developed in more detail? Which image strikes you as a cliché? How could the poet write “through” the cliché?

3) Mark one or two lines in the poem that you think stand out above all others. What did you like about this line? Is it located in the most effective position? How does it make use of tension? How does it make use of meter? Which line strikes you as more random than it needs to be? Suggest another layer of choice the writer might consider in his or her lineation.

4) How effective or ineffective is the writer’s word choice/diction? Which particular words should the writer reconsider? Why should she/he reconsider these (connotation, sound, consistency of voice)?

5) What uses of sound--rhyme, alliteration, assonance, etc.--fit well with the sense of the poem? What choices seem overdone or under-considered?

6) Characterize the voice in this poem. Is it strong, reflective, consistent or inconsistent? How could the writer better establish the speaker’s voice?

7) Which use of figurative language in the poem drew your attention (metaphor, simile, personification, etc.)? Where could this writer consider using a stronger or weaker comparison? Where do you see mixed or inconsistent figures of speech that need to be made more consistent?

Harder Revision(s) (answer at least one of these and no more than two)

1) What is the central emotional core of the poem? Where do you think the writer best demonstrates this as a grounded/embodied feeling? Where does he or she miss a chance to emphasize or offer more connection to this sensation? Where is he sentimental?

2) What thought/idea/term in this poem is used in a lazy way? Where could it be better defined or made vivid? In whose voice could this abstraction/thought be better conveyed?

3) Where do you find the poet moralizing? Has she earned this? Tell her what she must do to talk to you this way.

4) Does this poem fit your understanding of ekphrasis or musical ekphrasis? Does it expand your sense of these kinds of poetry? Tell the writer what he has done to make you clarify or revise your definition.

Friday, December 7, 2007

Wednesday, December 5, 2007

Michelangelo's Seizure

Michelangelo's Seizure--Steve Gehrke

When it happened, finally,

on the preparation bridge,

where he had stood all morning

grinding the pigments, grooming

his brush-tips to a fine point

so that he could thread Eve's hair

like a serpent down her back,

his head rocked forward on the bell-chain

of his spine, the catwalks

rattling as he fell, a paint-

bowl splattering the ceiling,

then spinning like a dying bird,

to the chapel floor, frightening

the assistant who—trained

in such matters—huffed up

the footbridge to wedge

the handle of a wooden brush

between the mouse-trap of the teeth,

to keep the master from biting off

his tongue. Did the choir-box

fill with angels? Did the master

feel the beast rising up in him

to devour the pearl of heaven

at the center of his brain? If you

were that assistant, kneeling

next to the stampeded body,

smelling the quicklime in the air,

the boiled milk of plaster, seeing him

tangled in the body's vines, voiceless,

strained, would you call it rapture?

The assistant didn't either, didn't even

consider it, or think to pray,

but sat watching as the spirit clattered

back inside of him, like a chandelier

lowered from a ceiling—

and when it was over, he thought

he heard the artist curse softly

as he surfaced, a small word, violent,

so that when the master walked outside

to get some air, the boy sat atop

the scaffolding, eating his orange

and letting the fruit peels fall,

like drips of flame, feeling freer

in a way, almost glad. Outside,

it was fall, the city proud

with chimneys. Ragged, clouds

of plaster in his beard, his mouth

hollow, aching like an empty purse,

Michelangelo could still hear

the tortured voices on the ceiling

calling out for completion,

amputated, each face shadowed

with his own, which he would paint,

one morning, with the witchcraft

hushed inside his veins,

onto the flayed skin of St.

Bartholomew, crumpled, fierce,

with two dead bugs crushed

into the paint, like that bit of terror,

he would think, sealed inside

of everything He makes. Now

he lifted his fingers to his lips,

to the wasp's nest of his mouth,

and withdrew, with the ease of spitting

out an apple stem, a tiny splinter

of wood that had sunk into his tongue.

Read a reviewof Steve Gehrke's entirely ekphrastic collection from U of Illinois Press.Of course you could always read Michelangelo's own sonnets.

Sunday, December 2, 2007

Saturday, December 1, 2007

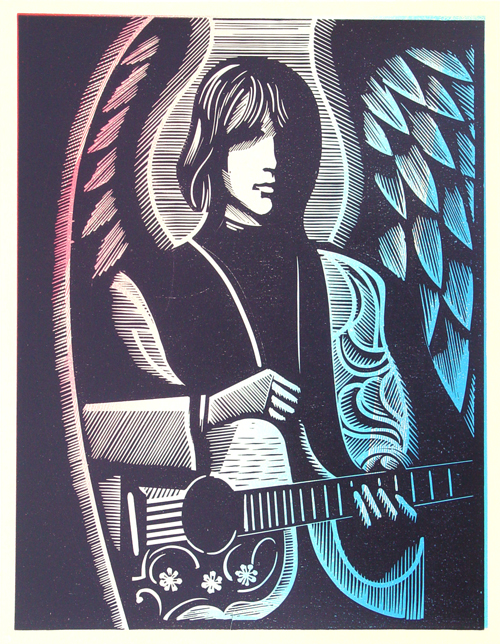

music as lonesome as I am

Bluefield Breakdown--Rick Mulkey

Where are you Clyde Moody, and you Elmer Bird,

"Banjo Man from Turkey Creek," and you Ed Haley,

and Dixie Lee singing in that high lonesome way?

I feel the shadow now upon me...

Come you angels and play those dusty strings.

You ain't gonna work that sawmill Brother Carter,

nor sleep in that Buchanon County mine. Clawhammer

some of that Cripple Creek song. Fiddle me a line

of "Chinquapin Hunting." Shout little Lulie, shout, shout.

I need to hear music as lonesome as I am,

I need to hear voices sing words I've forgotten.

This valley's much too dark now.

Sunset right beside us, sunrise too far away.

I haven't heard a tipple creak all day,

and everyone I loved left

on the last Norfolk & Southern train.

from Toward Any Darkness (Word Press, 2007)

Where are you Clyde Moody, and you Elmer Bird,

"Banjo Man from Turkey Creek," and you Ed Haley,

and Dixie Lee singing in that high lonesome way?

I feel the shadow now upon me...

Come you angels and play those dusty strings.

You ain't gonna work that sawmill Brother Carter,

nor sleep in that Buchanon County mine. Clawhammer

some of that Cripple Creek song. Fiddle me a line

of "Chinquapin Hunting." Shout little Lulie, shout, shout.

I need to hear music as lonesome as I am,

I need to hear voices sing words I've forgotten.

This valley's much too dark now.

Sunset right beside us, sunrise too far away.

I haven't heard a tipple creak all day,

and everyone I loved left

on the last Norfolk & Southern train.

from Toward Any Darkness (Word Press, 2007)

Wednesday, November 28, 2007

from The Gravity Soundtrack

Here's the poem I read in yesterday's class from Erin Keane's The Gravity Soundtrack.

A bit more about Gram Parsons and his strange death may or may not be necessary to make your way into the poem.

Grievous Angel--Erin Keane

Who’s to say what’s serious, a joke made

at the edge of a friend’s grave? A promise.

The desert, a gas can, a light. A corpse

has no value, you’ll only be charged

with coffin theft: a misdemeanor, a prank,

setting a body on fire. My bodysnatcher,

my brother, haven’t we done this, already,

too many times? The many ways to scatter

a burden: hot ash wind lifting like a UFO’s

beam, lizards tracking me, charred, through

the Joshua Tree sand. The left bits swept up,

mailed to New Orleans, God’s own singer

put down near the highway. A laugh, at last:

ours—I rest here. Me reflected in your pupils,

orange, blossoming. I couldn’t give you

anything to hold, so take this wakeful night,

know it can't make sense. What's left? At least

make it a good story. An offering, one last.

Other excerpts from the collection can be found here.

Saturday, November 24, 2007

Why We Sing--John Bell

I've mentioned John Bell a number of times as we've discussed hymns and hymn writing in class. A member of the Iona Community in the UK, Bell is, to my mind, one of the best writers and teachers of contemporary hymnody. Two of his books, The Singing Thing (2000) and The Singing Thing Too (2007) form essential reading for those interested in how the church might sing well and with integrity. Below is a summary of his reasons for singing (and reasons why some of us don't sing) from The Singing Thing. The non-Bell quotations are my additions. I hope this spurs you along as you try your hand at hymn lyrics.

Ten Reasons We Sing*

“Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly in all wisdom; teaching and admonishing one another in psalms and hymns and spiritual songs, singing with grace in your hearts to the Lord.” --Colossians 3:16, KJV

1) We sing because we can, because it is a uniquely and essentially human thing to do.

“Music is about as physical as it gets: your essential rhythm is your heartbeat; your essential sound, the breath. We’re walking temples of noise, and when you add tender hearts to this mix, it somehow lets us meet in places we couldn’t get to any other way.” --Anne Lamott, from Traveling Mercies: Some Thoughts on Faith

2) We sing to create and reflect our identity.

“Singing functions for Mennonites as sacraments do in liturgical churches. Singing is the moment when we encounter God most directly. We taste God, we touch God when we sing. It is an occasion of profound spiritual experience, and we would be bereft without it. --Marlene Kropf and Kenneth Nafziger, from Singing: A Mennonite Voice.

“It is not you that sings, it is the church that is singing, and you, as a member. . . may share in its song. Thus all singing together that is right must serve to widen our spiritual horizon, make us see our little company as a member of the great Christian church on earth, and help us willingly and gladly to join our singing, be it feeble or good, to the song of the church. --Dietrich Bonhoeffer, from Life Together

3) We sing to express emotion.

“Music is to be praised as second only to the Word of God because by music are all the emotions swayed. Nothing on earth is more mighty to make the sad happy and the happy sad, to hearten the downcast, mellow the overweening, temper the exuberant, or mollify the vengeful.” –Martin Luther

4) We sing to express language.

What language shall I borrow to thank Thee, dearest friend,

For this Thy dying sorrow, Thy pity without end?

O make me Thine forever, and should I fainting be,

Lord, let me never, never outlive my love to Thee.

-- Bernard of Clairvaux, 1153; trans lated from Latin to German by Paul Gerhardt; and from Latin to English by James W. Alexander, 1830.

5) We sing to remember our past (and thus to shape our future).

“We are creatures of our past. We cannot be separated from it, and although we cannot always remember it, songs will unexpectedly summon portions of it into mind. If this is true of secular ballads, it is even more true of Christian songs and hymns, especially those which have been in currency since childhood. . . . What we learn in childhood we retain all our life and the images of God we receive from such songs will determine our faith and theology. That means that whenever anyone teaches a child a hymn or religious song, they may be preparing that child to meet his or her Maker. Does that seem too extreme?”

--John Bell, from The Singing Thing

“Singing in church is not the religious equivalent of television commercials to offer relief between prolonged periods of speech. Singing in church is a means by which the worship of those committed to Christ is enabled to happen with engagement and integrity.” –John Bell

6) We sing to tell stories.

7) We sing to shape the future.

8) We sing to enable work.

9) We sing to exercise our creativity.

10) We sing to give of ourselves.

Four Reasons Why Some of Us Don’t/Won’t Sing*

1) Vocal Disenfranchisement

“God . . . never asks people to do what they cannot. When God asks us to sin a new song, it is because God believes that we can. Is it as simple as this? Yes. It is as simple as this. The much more complex matter is for musicians to stop telling children and teenagers whose voices haven’t matured or are temporarily dysfunctional that they can’t sing. And it is even more difficult for musicians—in the face of their academic training and desire to demonstrate choral and vocal technique---to believe that simply by including everyone in the song, and by willing people to sing together, the groaners and the tuneless folk will find their voice.” --John Bell

“The rise of gospel pop also revealed a popular redefinition of the emotions deemed proper in worship. Reverence, contrition, and perhaps a subdued sense of exaltation and had been the only approved emotions in Protestant worship . . . But the new music demonstrated that exuberant excitement and other ‘thrills’ could be a legitimate part of worship. While traditionalists tried to induce reverence by making church music as different from popular fare as possible, evangelical teenagers tried to make worship more fun than a school dance . . . gospel pop functioned as an emotional ‘cover’ that allowed the ecstatic release found in black, Pentecostal, and holiness spiritualities to reenter the world of white evangelical restraint. Theological judgments will necessarily vary regarding how faithfully this music communicated the essence of the Christian faith.”

--Thomas E. Berger, “The Youth for Christ Movement and American Congregational Singing”

2) The Fallout from a Performance Culture

“ Congregational song is a gift of God, with power to uplift, transform, refresh and recreate the heart and soul. As good stewards of the musical gifts God has given us we sing with energy and vigor. Our music-making usues the talents, skills and resources of the congregation. Worship is a participatory activity, a congregational activity, not a performance by the pastor or worship leader or choir or worship band or song leader.” --Heidi Regier Kreider, from “Music in the Church

“In order that the people of God can be summoned to sing, the Church has to ensure that it does not, in the way of the world, get performance and participation mixed up. In this respect, it would be salutary to enquire of church musicians what proportion of their time is spent preparing to engage the whole congregation in song over against the time spent honing their own instrumental or vocal skills.” --John Bell

3) Places and Spaces

“A new organ, a new praise group, a bigger choir will not make a congregation sing any better if they are encouraged to sit all over a church, preserving the maximum private space around themselves. Public worship is not private devotion, and ministers and musicians have to be clear that encouraging this kind if individualism is the enemy of corporate liturgy and community singing. When people are encouraged to sit close to each other and sing together, they will make a good sound even in the dullest of buildings . . . but where they loll in splendid isolation in their favoured pews, they simply cannot fulfill the mandate to praise their Maker as the community of God has chosen.”--–John Bell

4) Bad Leadership

“Worshiping God is not simply a good thing to do; it is a necessary thing to do to be human. The most profound statement that can be made about us is that we need to join with others in bowing before God in worshipful acts of devotion, praise, obedience, thanksgiving, and petition. What is more, when all the clutter is cleared away from our lives, we human beings do not merely need to engage in corporate worship; we truly want to worship in communion with others. All of us know somewhere in our hearts that we are not whole without such worship, and we hunger to engage in that practice. Thus, planners of worship do not make worship meaningful; worship is already meaningful. We do not manufacture worship that addresses people’s deepest needs; true worship already meets those needs. Our job, then, is to get the distortions out of the way and to plan worship that is authentic, that does not obscure, indeed that magnifies, those aspects of true worship that draw people yearning to be whole. - Thomas G. Long, Beyond the Worship Wars: Building Vital and Faithful Worship

*Adapted from John Bell’s The Singing Thing: A Case for Congregational Song. Chicago: GIA Publications, 2000.

Two by Stephen Frech

Poet Stephen Frech has written an entire collection of poems based on the life and paintings of Rembrandt. A number of these could be seen as, in part, ekphrastic midrash, a faithful, fervent troubling of scripture for meaning and insight through the further refraction/commentary of Rembrandt's many biblical paintings. Here are two.

Christ at Emmaus—Stephen Frech

One asked the stranger to divide the bread

and the flame wavered as if a breeze crept in.

Pausing for a moment, the inn’s day done,

he listened to the distant kitchen clatter,

a woman bent over a basin

scrubbing the day’s grime from new pots—

tomorrow, who can discern yesterday’s from today’s?

So the stranger took the loaf in both hands,

measured with his thumbs the seam

where he intended to break it,

showed it to one many saying, “This is for you.”

As the crust tore, the cup tipped

and spilled its wine that ran the length

and seeped through the cracks of the table’s planks.

Knowing him at last, am I the one froze in surprise

or the other, fallen to my knees, my eyes cast down

seeing some far field I’ve never lost sight of

and that, if only I’d set out, a day’s walking

would have brought to me.

The Adoration of The Shepherds—Stephen Frech

They entered slowly like birds wanting bread.

Unlike any other seed they know,

it stirs a hunger a day of feeding won’t sate,

a longing so desperate that, skittish, with quick eyes

watchful for the other fist,

they risk feeding from your hand.

The smell of the barn fouled the nostrils:

the day had been long and hot,

the animals labored hard.

Crushed bindweed dried on the hooves of cattle;

the horse’s collar hung on the wall,

its padded leather still damp and rip with horse brine.

And hay, just on the far side of fermenting,

spike the air and kept the cows dreamy and docile.

An old man carries a dim lamp into the light of the barn

and the flame is merely flame now—a busy sliver.

It hardly casts shadows of its own;

its light barely reaches the rotting loft boards.

He hadn’t expected this, not at all:

a new mother, so young and at ease

with the baby as only young mothers can be,

generous with all the strangers craning to take a look.

She doesn’t know—how could she?

The shadow on her breast is only of her hand.

from If Not for These Wrinkles of Darkness (White Pine Press, 2001

Friday, November 23, 2007

Rembrandt: Midrash and Icon

See the power point on Rembrandt: Midrash and Icon from Tuesday's class. Also, Ryan Pendell's blog. Much more to come.

Thursday, November 15, 2007

The Girl Who Became a Tom Waits Song

THE GIRL WHO BECAME A TOM WAITS SONG--Annalynn Hammond

It must've happened when no one was looking,

' cause all of a sudden she was a walking accordion,

her arms a pair of slide trombones. There was a pipe organ

in her chest, a bowed saw between her legs

and two tiny midgets appeared on her shoulders

to play her earrings as cymbals. Her trachea

was a mineshaft, her lungs were made of iron ore

and Tom, he was riding on her back,

tipping his hat to a passing parade.

read the rest at Diagram

In Your Lap

If you have time/resources, oh students of mine, go to the Chicago Symphony concert on campus! And write about it.

It looks like, tonight, you could also go to the Jazz Ensemble Fall Concert, or to Greg Halvorsen Schreck's photography exhibit and gallery talk.

P. S. Someone post a list of other live events on campus, in the area you think we should attend?

"The one who sings with me is my brother"

Here's Mark Noll on the unifying and divisive history of Christian hymnody:

An old German proverb runs: "Wer spricht mit mir ist mein Mitmensch; wer singt mit mir ist mein Bruder" (the one who speaks with me is my fellow human; the one who sings with me is my brother). In the world Christian community today, nothing defines "brotherhood" more obviously than singing. As it was in the beginning of the limited Christian pluralism in 16th-century Europe, so it remains in the nearly unbounded Christian pluralism of the 21st century. As soon as there were Protestants to be differentiated from Catholics, Calvinists from Lutherans, Anabaptists from Lutherans and Calvinists, Anglicans from Roman Catholics and other Protestants—so soon did singing become the powerful two-sided reality that it continues to be.

One reality was that believers who together sang the same hymns in the same way came to experience very strong ties with each other and even stronger rooting in Christianity. Psalm singing nerved Huguenots to face death and devastation during France's violent religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries. Palestrina gave an incalculable boost to the Counter-Reformation when he provided masses, hymns, litanies, and magnificats that for many Roman Catholics became as expressive of their faith as the congregational singing of Protestants was of theirs. In his fine book Singing the Gospel, Christopher Boyd Brown has shown that Bohemian Lutherans survived several generations of imperial Catholic pressure because families and lay groups were so much strengthened by the hymnody of Luther and his tradition.

Anabaptism was a movement of song—non-instrumental, non-clerical, non-élitist—as well as movement of belief; when Brethren or Mennonites sang, unaccompanied and in free form, the hymns of Michael Sattler, who was martyred in 1527 for his Anabaptist beliefs, they were affirming who they were as Christian believers and who they were not.

Which brings us to the second reality. As much as hymn singing has always been one of the most effective builders of Christian community, it has also always been one of the strongest dividers of Christian communities. In the early decades of the Reformation, Calvinists broke with Lutherans over several important matters, but one was existentially apparent at every gathering for worship: the singing. Lutherans sang hymns that with considerable freedom expressed their understanding of the gospel (like Luther's "A Mighty Fortress" or "From Heaven High I Come to You"), and they often sang them with choirs, organs, and full instrumentation. Calvinists, by contrast, sang the psalms paraphrased and with minimal or no instrumental accompaniment (like the 100th Psalm, "All people that on earth do dwell," which was prepared by William Kethe for English and Scottish exiles who had taken refuge in Calvin's Geneva during the persecutions of England's Catholic Mary Tudor). However natural it may now seem for Protestant hymnals to contain both Luther's "A Mighty Fortress" and Kethe's "Old One Hundredth," in fact it took more than two centuries of contentious Protestant history to overcome the visceral antagonism to "non-scriptural" hymns that prevailed widely in the English-speaking world. It was even longer before organs, choirs, and instrumental accompaniment were accepted.

Donald Hall on Poetry and Ambition

Donald Hall, from his (in)famous Poetry and Ambition

So the workshop answers the need for a cafe. But I called it the institutionalized cafe, and it differs from the Parisian version by instituting requirements and by hiring and paying mentors. Workshop mentors even make assignments: "Write a persona poem in the voice of a dead ancestor." "Make a poem containing these ten words in this order with as many other words as you wish." "Write a poem without adjectives, or without prepositions, or without content. . . ." These formulas, everyone says, are a whole lot of fun. . . . They also reduce poetry to a parlor game; they trivialize and make safe-seeming the real terrors of real art. This reduction-by-formula is not accidental. We play these games in order to reduce poetry to a parlor game. Games serve to democratize, to soften, and to standardize; they are repellent. Although in theory workshops serve a useful purpose in gathering young artists together, workshop practices enforce the McPoem.

This is your contrary assignment: Be as good a poet as George Herbert. Take as long as you wish.

So does this mean we can't teach young poets by such means? Is that all we can do, say, "see that great poet? go be like her!" My students are smart young women and men. They know the difference between an excursion helping them to see and a poem that teaches them something in its making, that resonates beyond the formula. Write a deep context poem. Sure. It's a trick, a pattern, a suggestion. And it comes along with "Don't write a Google-poem, a wiki-poem." And then we talk about that. And then they go to an American lit class and meet the unilimited ambition of Whitman and Melville. And the uncertainty.

Coming soon--"how not to write a google poem" and "what can be taught and when."

dw

So the workshop answers the need for a cafe. But I called it the institutionalized cafe, and it differs from the Parisian version by instituting requirements and by hiring and paying mentors. Workshop mentors even make assignments: "Write a persona poem in the voice of a dead ancestor." "Make a poem containing these ten words in this order with as many other words as you wish." "Write a poem without adjectives, or without prepositions, or without content. . . ." These formulas, everyone says, are a whole lot of fun. . . . They also reduce poetry to a parlor game; they trivialize and make safe-seeming the real terrors of real art. This reduction-by-formula is not accidental. We play these games in order to reduce poetry to a parlor game. Games serve to democratize, to soften, and to standardize; they are repellent. Although in theory workshops serve a useful purpose in gathering young artists together, workshop practices enforce the McPoem.

This is your contrary assignment: Be as good a poet as George Herbert. Take as long as you wish.

So does this mean we can't teach young poets by such means? Is that all we can do, say, "see that great poet? go be like her!" My students are smart young women and men. They know the difference between an excursion helping them to see and a poem that teaches them something in its making, that resonates beyond the formula. Write a deep context poem. Sure. It's a trick, a pattern, a suggestion. And it comes along with "Don't write a Google-poem, a wiki-poem." And then we talk about that. And then they go to an American lit class and meet the unilimited ambition of Whitman and Melville. And the uncertainty.

Coming soon--"how not to write a google poem" and "what can be taught and when."

dw

Tuesday, November 13, 2007

Rely on the cantus firmus

Two quotations taken from Dietrich Boenhoeffer's Letters and Papers from Prison, in which he uses the analogy of the fugue to explore our fragmentary lives:

1) There’s always the danger in all strong, erotic love that one may love what I might call the polyphony of life. What I mean is that God wants us to love him eternally with out whole hearts—not in such a way as to injure or weaken our earthly love, but to provide a kind of cantus firmus to which the other melodies of life provide the counterpoint. One of these contrapuntal themes (which have their own complete independence but are yet related to the cantus firmus) is earthly affection. Even in the Bible we have the Song of Songs; and really one can imagine no more ardent, passionate, sensual love than is portrayed there. . . . It is a good thing that that book is in the Bible, in face of all those who believe that the restraint of passion is Christian. (Where is there such restraint in the Old Testament?) Where the cantus firmus is clear and plain, the counterpoint can be developed to its limits. The two are “undivided and yet distinct” in the words of the Chalcedonian Definition, like Chirst and his divine and human natures. May not the attraction and importance of polyphony in music consist in its being a musical reflection of this Christological face and therefore of our vita Christiana? This thought didn’t occur to me until after your visit yesterday. Do you see what I’m driving at? I wanted to tell you to have a good, clear cantus firmus ; that is the only way to a full and perfect sound, when the counterpoint has a firm support and can’t come adrift or get out of tune, while remaining a distinct whole in its own right. Only a polyphony of this kind can give life a wholeness and at the same time assure us that nothing calamitous can happen as long as the cantus firmus is kept going . . . . Please, Eberhard, do not fear and hate the separation, if it should come with all its dangers, but rely on the cantus firmus. (166-67)

2) The important thing today is that we should be able to discern from the fragment of our life how the whole was arranged and planned, and what material it consists of. For really, there are some fragments that are only worth throwing into the dustbin (even a decent ‘hell’ is too good for them), and others whose importance lasts for centuries, because their completion can only be a matter for God, and so they are fragments that must be fragments. I think for example of the Art of the Fugue. If our life also is only a slightest reflection of such a fragment, in which at least for a short while the various themes, growing ever stronger, harmonize, and in which the great counterpoint is held on to from beginning to end so that finally, after the breaking-off point, the chorale Vor deinen Thron tret ich hiermit can still be intoned, then we do not wish to complain about our fragmentary life, but even be glad for it. (219)

Monday, November 12, 2007

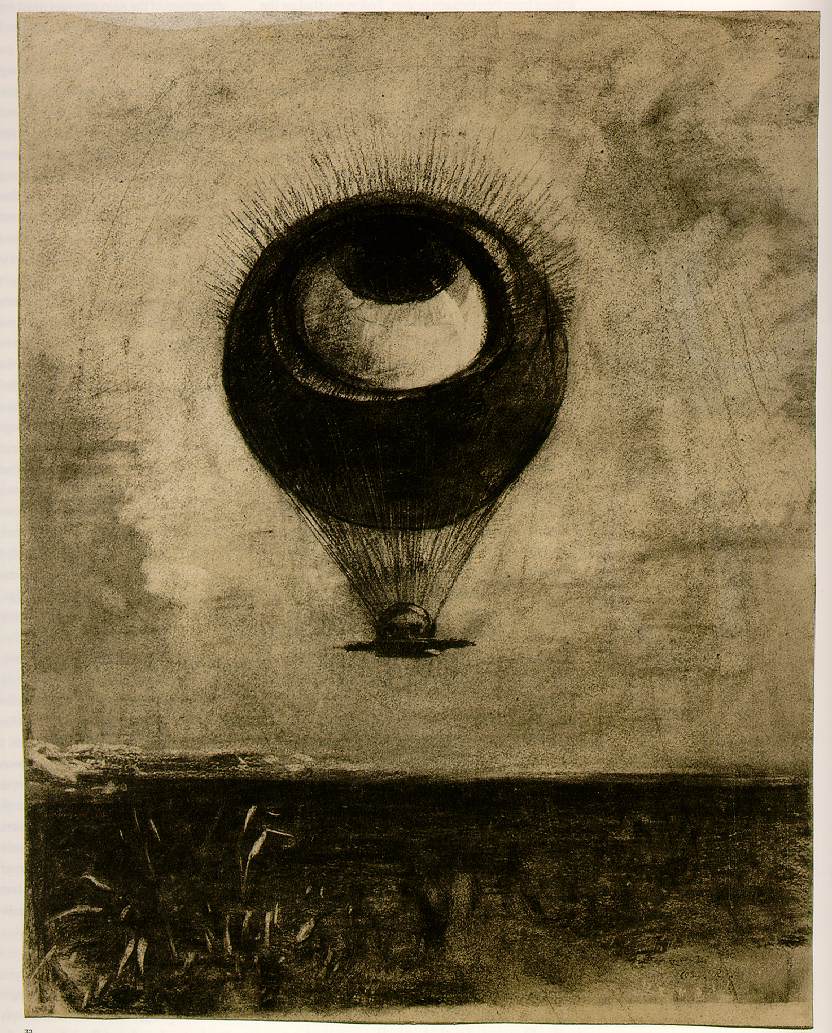

Basic Poetic(s) Question(s)--The Visual Ear

In a review of Mary Jo Bang's The Eye Like a Strange Balloon, Donna Stonecipher raises the/a key poetic(s) question for ekphrastic poetry: "Must I know the work of art to “get” the poem? How much am I missing if I don’t know it?" In other terms, can/does the poem stand on its own and does that matter. Stonecipher rightly describes ekphrasis as "a wonderfully elastic process" and suggests that "Only an art fiend (and Bang herself) would know all the artworks in question, but Bang is so meticulous that this fact doesn’t detract from the pleasures of the poems. Reading her work is such an intensely visual experience, in fact, that trying to keep one picture in mind while being presented with picture after picture in the poems would be pretty much impossible. "

So the spinning and confusion and pleasures of visual discovery in language make the poems, at least for Stonecipher. She

traces the means of discovery in Bang's work and concludes "that the poems proceed as much by sound as by sight. One uses one’s 'visual ear' to read her poems. Puns and double entendres turn into images. Images cede themselves to sonic grandeur. It is this high-stakes game of the visual and the aural, and their interplay as in a whirling two-butterfly mating dance, that give Bang’s poems their particular charge."

Here's the book's title poem, based on a piece by Odilon Redon.

The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity--Mary Jo Bang

We were going toward nothing

all along. Honing the acoustics,

heralding the instant

shifts, horizontal to vertical, particle

to plexus, morning to late,

lunch to later yet, instant to over. Done

to overdone. And all against

a pet store cacophony, the roof withstanding

its heavy snow load. So, winter. And still,

ambition to otherwise and a forest of wishes.

Meager the music floating over.

The car in the driveway. In the P-lot, or curbside.

A building overlooking an estuary,

inspired by a lighthouse.

Always asking, Has this this been built?

Or is it all process?

Molecular coherence, a dramatic canopy,

cafeteria din, audacious design. Or humble.

Saying, We ask only to be compared to the ant-

erior cruciate ligament. So simple. So elegant.

Animated detail, data from digital.

But of course there is also longstanding evil.

The spider speaking

to the fly, Come in, come in.

Overcoming timidity. Overlooking consequence.

Finally ending

with the future. Take comfort.

You were going nowhere. You were not alone.

You were one

of a body curled on a beach. Near sleep

on a balcony. The negative night in a small town or part

of an urban abstraction.

Looking up

at the billboard hummingbird,

its enormous beak. There’s a song that goes . . .

And then the curtain drops.

Odilon Redon, The Eye Like a Strange Balloon

Mounts Toward Infinity, charcoal on paper, 1882

So the spinning and confusion and pleasures of visual discovery in language make the poems, at least for Stonecipher. She

traces the means of discovery in Bang's work and concludes "that the poems proceed as much by sound as by sight. One uses one’s 'visual ear' to read her poems. Puns and double entendres turn into images. Images cede themselves to sonic grandeur. It is this high-stakes game of the visual and the aural, and their interplay as in a whirling two-butterfly mating dance, that give Bang’s poems their particular charge."

Here's the book's title poem, based on a piece by Odilon Redon.

The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity--Mary Jo Bang

We were going toward nothing

all along. Honing the acoustics,

heralding the instant

shifts, horizontal to vertical, particle

to plexus, morning to late,

lunch to later yet, instant to over. Done

to overdone. And all against

a pet store cacophony, the roof withstanding

its heavy snow load. So, winter. And still,

ambition to otherwise and a forest of wishes.

Meager the music floating over.

The car in the driveway. In the P-lot, or curbside.

A building overlooking an estuary,

inspired by a lighthouse.

Always asking, Has this this been built?

Or is it all process?

Molecular coherence, a dramatic canopy,

cafeteria din, audacious design. Or humble.

Saying, We ask only to be compared to the ant-

erior cruciate ligament. So simple. So elegant.

Animated detail, data from digital.

But of course there is also longstanding evil.

The spider speaking

to the fly, Come in, come in.

Overcoming timidity. Overlooking consequence.

Finally ending

with the future. Take comfort.

You were going nowhere. You were not alone.

You were one

of a body curled on a beach. Near sleep

on a balcony. The negative night in a small town or part

of an urban abstraction.

Looking up

at the billboard hummingbird,

its enormous beak. There’s a song that goes . . .

And then the curtain drops.

Odilon Redon, The Eye Like a Strange Balloon

Mounts Toward Infinity, charcoal on paper, 1882

A much hipper playlist

Because my playlist is truly odd, I thought you'd like a much hipper playlist from a much hipper poet. Kevin Young, who edited our little Jazz Poems anthology, offers this list . I know about one-eighth of these.

To go along with the playlist I gave you, here's Young's Satchmo.

To go along with the playlist I gave you, here's Young's Satchmo.

Thursday, November 8, 2007

And the last few of these DJPH poems for now

Poem for David Hooker—Rachel A.

You have to make your inspiration up;

my art's a job, like any other craft.

Collage-like sculpture, simple lovely cup,

I shape them both, draft after thumb-worn draft,

from clay bricks, in the place of pen and book.

Back in my undergrad days I'd have laughed

to see the way my work would one day look:

wake early, feed the children, sit and stare

at things for half an hour. I'd have took

offense if you'd described my present hair,

my quiet clothes. smudged now with dust, not ink.

Today I'll shave a centimeter there,

here dab a touch of blue. Might do, I think.

Poetry stands just on pottery's brink—

one claw held back, one cross taken back up.

In His Studio--Laura M.

He has a smallish set of wings—

envisioned in a plaster mold—

which don’t belong to anything.

No sinew’d shoulders, nothing—

an absence

of wings.

Is there in mold-land, hid somewhere,

a waiting plaster angel? Will

he find it, claying spare to spare—

a space of wings—raw, cased-in air—

the absence—

of angel?

One Thousand Pounds of Clay—Charis T.

A line is drawn,

Collage created, paint painted

Before the one-thousand pounds

Of clay hits

The concrete floor

Or table.

Carton blue,

And red hues

Eyes of a dog,

A preying mantis

Mantled on the table.

The gray clay

Now portrays

A sarcastic smile

A solemn cry

And the KKK’s

Pinkish eyes

Chaos weaved

In and out

The leg’s about

A foot long

And bends on an arm,

A hand holding a gun.

On Visiting David Hooker’s Studio--Marjorie H.

forget the wheel throwing

– not the pot but –

itself out the window.

process is slow and nothing

like Mr. Rogers concept

– of the art of creating art –

we learned. Instead it is full

of sitting and staring at

– but not sleeping on –

a Britney Spears pillow

and Jesus the son of the Virgin

combine into Britney

– not Madonna –

like a virgin and Jesus her son.

Labels:

artistic process,

Charis T.,

David Hooker,

guernica,

Laura M,

Marjorie H.,

poems in process,

Rachel A.

Bekah Explores D. Hooker's Brain

David Hooker’s Studio—Bekah T.

1

Failed paintings

and his own strict sense of honor.

Art is reams of images:

Dogs,

Scuba divers,

Guernica,

Slave ship diagram,

Bird cage,

Cartoons.

Jesus

And Britney Spears

On a pillow.

Is it right or is it easy?

When the images click

Do they tell a story, ask a question,

Present an answer in three dimensional space?

Resisting the pull of the semester

He lets things sit, rest in his mind

Images colliding with images

On paper, on canvas

Till they begin to take

Concrete clay shape

And even then

The deer is in danger of decapitation

The cat of becoming a Klan member

The Statue of Liberty of losing its head.

2--Waiting the Idea Out

If I sit

Long enough,

If I work

On three casts of dogs

That all break at firing

If I wait

The idea out

Maybe It’ll change.

I wont have to decapitate

The lawn ornament deer,

paint a stormy sky,

Or confuse Guernica with a cartoon.

Making art is having

The courage

To do the ungodly,

Profane the sacred.

Mix cults and crosses,

Dogs and freedom,

A praying mantis

And the cartoon south.

Sometimes the piece is too demanding

And calls me to a direction I am not quite

Ready for.

I am not that brave or that strong.

Check back in three years

After college, a mortgage,

Two kids and a career.

When I get my first gray hairs

And gain the age required for

Following sacrilege.

Maybe I’ll be ready then

Maybe.

Maybe.

3

It’s too hot to work in a room of 2,000 degree creativity, and a firing squad

Pacing outside. Dogs fly through canvases and eat the statue of Liberty. It’s

Getting too hot as Brittney Spears covers Jesus, and Guernica holds a cartoon gun.

My hands are bleeding

What happens

The fire is too hot, the space too cold. There are miles and miles in between antlers

And doves. Whole cities exist between headless statues and dead

Pet

Dogs. What happens

The mind turns and tomorrow and three years from now

Sit for hours and absorb one image, realize the color, the cut

It’s wrong. It’s easy not right

Easy, too easy

Smash 2,000 lbs of clay into cookie cutter lawn ornament molds

Something will turn out

Something

Thing

Some point of combined interest,

Asking a question

I don’t know what it means.

Labels:

artistic process,

Bekah T.,

David Hooker,

poems in process

The now that bridges the abyss

Music has also played a crucial role in Sacks's work as a neurologist. In his writings, he uses music as a metaphor for his unusual approach to medicine. He cites a Novalis aphorism—"Every disease is a musical problem; every cure is a musical solution"—in several books, usually when discussing the therapeutic powers of music. But it's clear that Sacks also believes in a deeper, less literal connection between medicine and music, which is why Musicophilia reads like a retrospective. Music encapsulates two of the most essential aspects of his work: listening and feeling. The art form is the model for his method. As a doctor, Sacks is exquisitely attentive, not just to the symptoms, but also to the person. He treats each patient like a piece of music, a complex creation that must be felt to be understood. Sacks listens intensely so that he can feel what it's like, so that he can develop an "intuitive sympathy" with the individual. It is this basic connection, a connection that defies explanation, that allows Sacks to heal his patients, letting them recover what has been lost: their sense of self.

from Jonah Lehrer's profile of the neurologist Oliver Sacks and his new work Musicophilia.

The first chapter, excerpted in the NY Times, narrates the experience of a surgeon struck by lightning who develops a deep desire for piano music, to both listen to and play it:

With this sudden onset of craving for piano music, he began to buy recordings and became especially enamored of a Vladimir Ashkenazy recording of Chopin favorites — the Military Polonaise, the Winter Wind Étude, the Black Key Étude, the A-flat Polonaise, the B-flat Minor Scherzo. [see Ashkenazy playing a Chopin etude] "I loved them all," Tony said. "I had the desire to play them. I ordered all the sheet music. At this point, one of our babysitters asked if she could store her piano in our house — so now, just when I craved one, a piano arrived, a nice little upright. It suited me fine. I could hardly read the music, could barely play, but I started to teach myself." It had been more than thirty years since the few piano lessons of his boyhood, and his fingers seemed stiff and awkward.

What fascinates me, in part, about Sacks and his work is how his examination suggests that music is not decoration but a different and basic way of knowing and experiencing the world. He writes near the end of the book about musicologist and performer Clive Wearing, who suffers from such terrible amnesia that he cannot remember his world moment to moment. He scribbles in a journal on page after page:

“I am awake” or “I am conscious,” entered again and again every few minutes. He would write: “2:10 P.M: This time properly awake. . . . 2:14 P.M: this time finally awake. . . . 2:35 P.M: this time completely awake,” along with negations of these statements: “At 9:40 P.M. I awoke for the first time, despite my previous claims.” This in turn was crossed out, followed by “I was fully conscious at 10:35 P.M., and awake for the first time in many, many weeks.” This in turn was cancelled out by the next entry.

This man who "no longer has any inner narrative," however, becomes, for the moments when he is playing a Bach prelude, "himself again and wholly alive." Music becomes for him the only continuous, linear "now" he has. As Sacks writes, in this man's disconnected world, music is "the 'now' that bridges the abyss."

Wednesday, November 7, 2007

A music poem? Discuss

ODE ON A GRECIAN URN--John Keats

Thou still unravished bride of quietness,

Thou foster child of silence and slow time,

Sylvan historian, who canst thus express

A flowery tale more sweetly than our rhyme:

What leaf-fringed legend haunts about thy shape

Of deities or mortals, or of both,

In Tempe or the dales of Arcady?

What men or gods are these? What maidens loath?

What mad pursuit? What struggle to escape?

What pipes and timbrels? What wild ecstasy?

Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard

Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on;

Not to the sensual ear, but, more endeared,

Pipe to the spirit dities of no tone.

Fair youth, beneath the trees, thou canst not leave

Thy song, nor ever can those trees be bare;

Bold Lover, never, never canst thou kiss,

Though winning near the goal---yet, do not grieve;

She cannot fade, though thou hast not thy bliss

Forever wilt thou love, and she be fair!

Ah, happy, happy boughs! that cannot shed

Your leaves, nor ever bid the Spring adieu;

And, happy melodist, unweari-ed,

Forever piping songs forever new;

More happy love! more happy, happy love!

Forever warm and still to be enjoyed,

Forever panting, and forever young;

All breathing human passion far above,

That leaves a heart high-sorrowful and cloyed,

A burning forehead, and a parching tongue.

Who are these coming to the sacrifice?

To what green altar, O mysterious priest,

Lead'st thou that heifer lowing at the skies,

And all her silken flanks with garlands dressed?

What little town by river or sea shore,

Or mountain-built with peaceful citadel,

Is emptied of this folk, this pious morn?

And, little town, thy streets for evermore

Will silent be; and not a soul to tell

Why thou art desolate, can e'er return.

O Attic shape! Fair attitude! with brede

Of marble men and maidens overwrought,

With forest branches and the trodden weed;

Thou, silent form, dost tease us out of thought

As doth eternity. Cold Pastoral!

When old age shall this generation waste,

Thou shalt remain, in midst of other woe

Than ours, a friend to man, to whom thou say'st,

"Beauty is truth, truth beauty"---that is all

Ye know on earth, and all ye need to know.

Through your ears and inside your mind

Sometimes when you are listening to a great jazz musician performing a long solo, you are experiencing his mind, moment by moment, as it shifts and decides, as it adds and reminds. This happens whether the player is a saxophone player or a bass player or a pianist. You are in there, where that other mind is. His mind is coming through your ears and inside your mind.

The first time I heard Charlie Parker playing Ornithology, I was delighted. I was about 11 years old. You are so much alone with your mind as a kid, so when you hear someone else's mind improvising, you feel an excitement you will never get from some music that just wants to keep a steady beat.

The first time I heard Charlie Parker playing Ornithology, I was delighted. I was about 11 years old. You are so much alone with your mind as a kid, so when you hear someone else's mind improvising, you feel an excitement you will never get from some music that just wants to keep a steady beat.

George Bowering, Canada's first poet laureate, from a This I Believe essay on NPR

The first time I heard Charlie Parker playing Ornithology, I was delighted. I was about 11 years old. You are so much alone with your mind as a kid, so when you hear someone else's mind improvising, you feel an excitement you will never get from some music that just wants to keep a steady beat.

The first time I heard Charlie Parker playing Ornithology, I was delighted. I was about 11 years old. You are so much alone with your mind as a kid, so when you hear someone else's mind improvising, you feel an excitement you will never get from some music that just wants to keep a steady beat.George Bowering, Canada's first poet laureate, from a This I Believe essay on NPR

Tuesday, November 6, 2007

Some DJPH poems

Our visit to David Hooker’s studio a couple of weeks back has resulted in a variety of very interesting poetic responses, some focused more on David’s work, some focused more on his process. Below is a sampling of what’s been written, with more to come (this is a request for students to send them to me electronically, so I can cut and paste rather than retype).

David’s work is included in a current exhibit at Loyola University in Chicago, the show for which he was making final preparations when he talked with us.

He'll also be giving a talk as part of the Humanities Brown Bag forum this Friday on campus. He claims not to like prose about his work, but you can find some of his drafts of artist statements (along with other ramblings) at his engaging blog.

Functional and Beautiful

For those of you looking for Christmas gifts, David is also busy finishing bowls and mugs that look lovely and functional.

Some of the Hooker Poems

I have been in a ceramics studio--Ian A.

I’ve been in a ceramics studio, yes

I have. And seen the halves of broken

halves of pre-configured clay, collected

in boxes and shelved behind, waiting

for your hammer and you

to sledge out their inconsistencies

like God, only not quite as gradually

as your “Gun-toting Guernica,” but

sometimes that thought can sit, subdued

for months if you fight it when you say

you lobbied for the loud, garbage on the walls

of your college dormitory, the poetry

you would write, such perfunctory verse

could never contain you,

but that’s just a hope to fill the waiting

like we’re waiting, but then it came to you,

yes you said, an idea to solidify

in the absence of could it be

a thousand, giving themselves up

to be the smashed bodies behind, waiting

even more for some kind of redemption

to come, only not quite as bloodily.

David Hooker’s mantis –Dayna C.

The legs force the sculpture

like his fingers in your jeans

whose pistol bruises

the arch of your back.

All the natural dangers

pervert into a man.

We bruise like peaches

and have. We’ve held

the rail at the Canyon,

our adrenaline tart,

because despite what we’ve said

where we’re standing

is the start of the fault.

An Unglazed Frame for Absence--Rachel H.

The ceramic dog, hangs

from a nail in my dusty studio wall,

with an absence for feet, framed

by marbled terra cotta bisque,

right to be naked, fired clay

rough against soft fingers.

Every glance of his master asked,

"Is it right, or is it easy?"

Each kneading touch questioned

if the dog should hang on the nail,

on the plain wall, patient for grief.

Clay—Jason A.

We have but dirt to form a wandering mind,

Brittle crust that shatters between fingers

The formless mud in which our members bind

All to build proud monuments! that linger…

Impregnable fortress against a Sea of Time

Like making bricks without straw, yet still

We grapple matter whose essence, unsublime

We are, enslave it to our sand-castle will,

To harmonize some grander whiteness, or truth

With scripted tablets formed by blood-stained hands

As though in word to ever will our youth,

In small clay ships to sail to starlit lands.

As The Captives, forming soul from rough-hewn stone

We have but adobe slums to call our own.

At First Glance You May Mistake His Artistic Genius for Postmodern Garble—Joe M.

His slightly random 3-

Dimensional cornucopia

Made of clay has a praying

Mantis, headless deer,

And “quick Draw McGraw”

Holds a silver gun,

But look at how he holds

The elbow in tension

Just barely above the base,

IE: (how Michelangelo held

Adam’s finger,

With the slightest space

From touching God)

His headless “Bob the Builder”

Creates intentional spa c e,

He has Britney Spears

And Jesus waiting on a mantel,

But nothing he shows us has he

Not seen before while driving

The highways of his mind,

Things at first, still life

Drenched in anecdotal glory,

His art expressing the tension in presence

And

Absence

How he speaks silently of

L

o

S

s

Labels:

artistic process,

David Hooker,

Dayna C.,

Ian A.,

Jason A.,

Joe M.,

poems in process,

Rachel H.

Saturday, November 3, 2007

Friday, November 2, 2007

HOW TO READ, AND PERHAPS ENJOY, VERY NEW POETRY

This article by Stephen Burt in The Believer is finally on line. I like this quotation:

The most important precepts are the simplest: look for a persona and a world, not for an argument or a plot. Enjoy double meanings: don’t feel you must choose between them. Ask what the disparate elements have in common—do they stand for one another, or for the same thing? Are they opposites, irreconcilable alternatives? Or do they fit together to represent a world? Look for self-descriptive or for frame-breaking moments, when the poem stops to tell you what it describes. (Classic Ashbery poems tend to end with these: “I will keep to myself. / I will not repeat others’ comments about me.”; “A randomness, a darkness of one’s own.”) Use your own frustration, or the poem’s apparent obliquity, as a tool: many of these poems include attacks on assumptions or pretenses that make ordinary conversational language, and newspaper prose, so smooth.

A couple of years ago, I got to interview Stephen for Avatar Review. He is very smart.I asked him a little bit about ekphrasis and he said:

At Yale in the 1990s, it seemed that everyone got attracted to ekphrasis—John Hollander had just written a book on the subject and taught classes on it. When I was writing some of those poems I was surrounded by poets and critics who took a strong interest in how poets could represent paintings (and sculpture and architecture and other visual arts).

I started writing poems about paintings before that, though—I wrote the Velazquez poem when I lived in Oxford. I like paintings. Paintings with character and narrative components—and you can find those components in apparently abstract artists, if you look; I often find them in Franz Kline—give poets a chance to sort-of make up, and sort-of discover, all sorts of stories and scenes. Ekphrases also let you flip back and forth between talking about a work of art as an object (and about the situation of its making), on the one hand, and talking about what the work depicts on the other—between, if I can use the terms here, diegetic and extradiegetic perspectives. I like poems (and critics) who can do those kinds of flips.

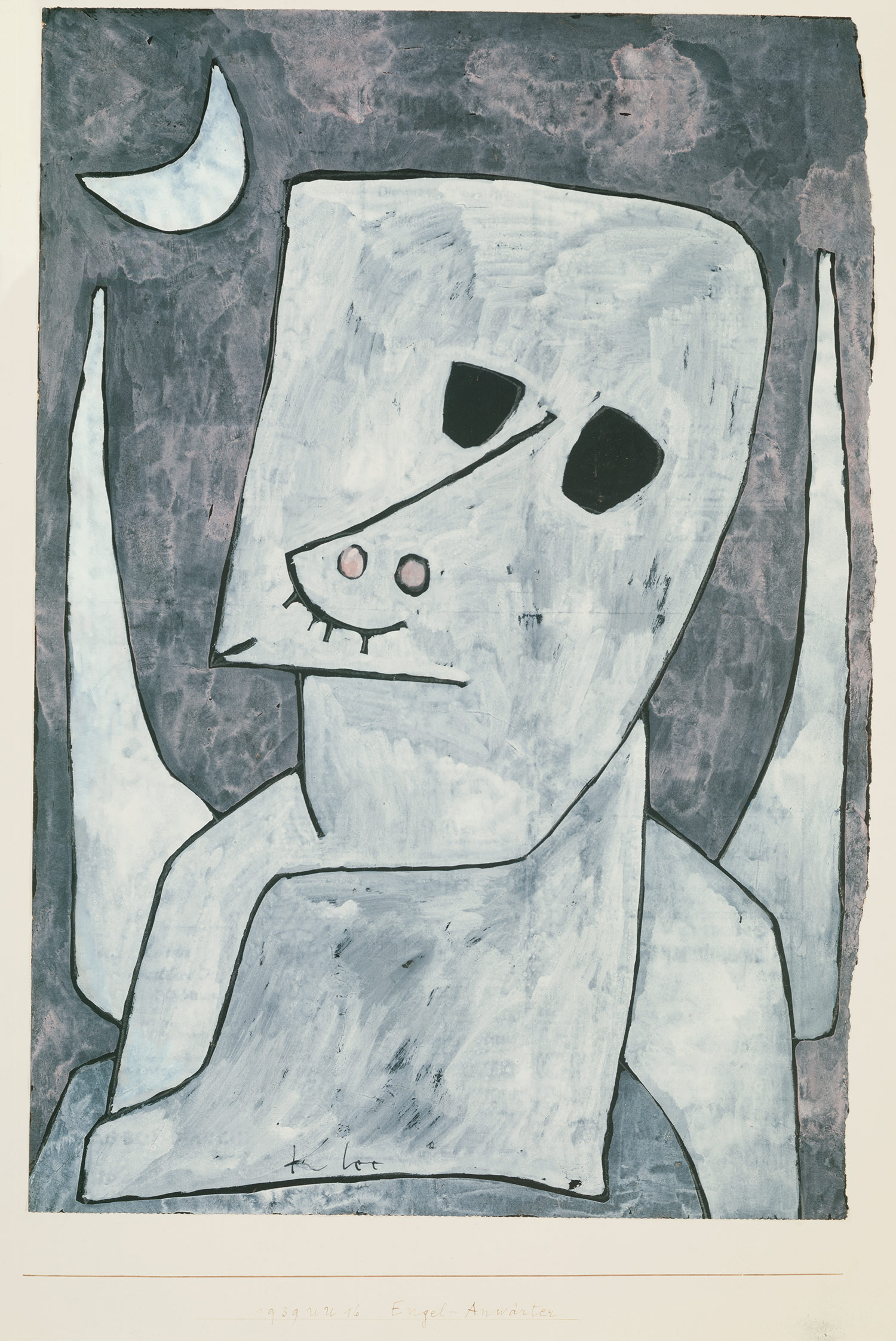

Sunday, October 28, 2007

Paul Klee and Keith Ratzlaff

One of the assignments for the end of the semester portfolio involves writing 3-4 poems on a single "subject." By single subject, I mean a series of pieces that look at the same piece of art, the same song, the same composer, or the same artist. (Notice, also, that I've reduced the required number of pieces to a minimum of 3).

You may want to take a different approach to a poem you've already composed. You may want to write several new pieces. We'll discuss your approach at your portfolio conference, but you'll want to already have some ideas in mind for class on Tuesday.

You may want to take a different approach to a poem you've already composed. You may want to write several new pieces. We'll discuss your approach at your portfolio conference, but you'll want to already have some ideas in mind for class on Tuesday.To ready ourselves for this assignment, we'll undertake several exercises and readings. First, we'll read and discuss Keith Ratzlaff's ekphrastic poetry collection, Dubious Angels. I've proposed a series of questions below that might help us into the book. First, though, you might want to know more about the writer and his approach to poetry, generally, and ekphrasis in particular. This multimedia interview from a few years back, including many mp3s of the poet reading from his poems, could offer much fuel for discussion about the poems and about the processes that lead to poems.

Second, you'll want to familiarize yourself a bit with Paul Klee and his work. The Klee Museum in Bern is a rich resource, including not only images but wonderful articles. (As it turns out, by poking around here I learned a great deal about Klee's interest in music.) A full, translated text of Klee's diaries

used to be available online, but I have not been able to find it recently.

used to be available online, but I have not been able to find it recently. Each poem in Ratzlaff's collection responds to an image of an angel created by Klee, mostly engravings made near the end of his life. Read Ratzlaff's preface, where he concludes, "I don't mean for the poems to speak for Paul Klee, nor have I wanted to turn the drawings into illustrations for the poems, or to make poems that are passive ekphrastic exercises."

Instead, the poet pitches his attempt as approximating Klee's "tragicomic voice and his jazz-like technique" as a way to give "the angels voices that do justice to the bodies Paul Klee created for them." Consider these questions as a way into the poems (and as a way of discovering means of your own for making similar poetic attempts).

1) Which angel poems seem mostly to be verbal transcripts of the images? What liberties does R. seem comfortable with in these pieces? What fidelities does he seem compelled to keep?

2) Which poems take the most fantastic leaps from the images? What fragments of the original do they retain? What vehicles carry the poems away (narratives, voices, forms)?

3) Note the uses Ratlzlaff makes of Klee's own writings (esp. in "Precocious Angel"). What do they do to the poem's voice and texture? Can you tell where the painter's voice starts and where the poet's takes over? How does this matter or not to you? How do masks work in such poems?

4) What use do you make of the notes? Should they be there? Why or why not? How do you think of the notes in relation to this quotation from Ratzlaff:

But no poet I know writes to make meaning, at least not initially. I write to make things, to control the world in some modest way. One thing many of my beginning literature students seem to believe is that poets are intentionally obscure. When students are really paranoid, they seem to believe poets mean for them personally to feel stupid. But that confuses the reader's problems with the writer's. I don't know any poet who is willfully obscure. When I'm in the act of writing a poem--and during that first ur-reading writers do--I'm convinced there's only one meaning for the poem and that the meaning is clear. Content isn't the issue, style is. Thus Klee's emphasis--always in the Sketchbook--is on the how. Criticism and theory, interpretive acts that rightfully belong to the reader, come later, hopefully traveling along at least some of the paths the work has cut out for it. When it works right, the poet and reader walk the path together.

5) How do you make sense of the collection's title, "Dubious Angels?" Read carefully the poem "Doubting Angel" on p. 63, which includes the lines: "Raising my hand / in the air as blessing / only requires / that I believe in air." What kinds of belief do the poems require of us? What kinds of belief do you require of your readers?

Addition

The note to "Last Earthly Step" refers to Walter Benjamin's discussion of Klee's "Angelus Novus." Here's that image and Benjamin's quotation:

“A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one perceives the angel of history. His face is towards the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

Walter Benjamin Theses on the Philosophy of History

Labels:

assignment update,

deep context,

Keith Ratzlaff,

Paul Klee

The Silence of the World Before Bach

The Silence of the World before Bach--Lars Gustafson

There must have been a world before

the Trio Sonata in D, a world before the A minor Partita,

but what kind of a world?

A Europe of vast empty spaces, unresounding,

everywhere unawakened instruments

where the Musical Offering, the Well-tempered Clavier

never passed across the keys.

Isolated churches

where the soprano-line of the Passion

never in helpless love twined round

the gentler movements of the flute,

broad soft landscapes

where nothing breaks the stillness

but old woodcutters' axes,

the healthy barking of strong dogs in winter

and, like a bell, skates biting into fresh ice;

the swallows whirring through summer air,

the shell resounding at the child's ear

and nowhere Bach nowhere Bach

the world in a skater's silence before Bach.

There must have been a world before

the Trio Sonata in D, a world before the A minor Partita,

but what kind of a world?

A Europe of vast empty spaces, unresounding,

everywhere unawakened instruments

where the Musical Offering, the Well-tempered Clavier

never passed across the keys.

Isolated churches

where the soprano-line of the Passion

never in helpless love twined round

the gentler movements of the flute,

broad soft landscapes

where nothing breaks the stillness

but old woodcutters' axes,

the healthy barking of strong dogs in winter

and, like a bell, skates biting into fresh ice;

the swallows whirring through summer air,

the shell resounding at the child's ear

and nowhere Bach nowhere Bach

the world in a skater's silence before Bach.

An Excerpt from a Coltrane Bio

Coltrane loved structure in music, and the science and theory of harmony; one of the ways he is remembered is as the champion student of jazz. But insofar as Coltrane's music has some extraordinary properties — the power to make you change your consciousness a little bit — we ought to widen the focus beyond the constructs of his music, his compositions, and his intellectual conceits. Eventually we can come around to the music's overall sound: first how it feels in the ear and later how it feels in the memory, as mass and as metaphor. Musical structure, for instance, can't contain morality. But sound, somehow, can. Coltrane's large, direct, vibratoless sound transmitted his basic desire: "that I'm supposed to grow to the best good that I can get to.

from Ben Ratliff's Coltrane: The Story of Sound

P. S. What's due on Tuesday, you ask? Read Ratzlaff's poems, come with a draft of a poem--either the David Hooker poem or something else, come ready to listen in class to some Bach and to be exposed to a piece of contextual detail that will lead to an in-class poem. Be thinking about your portfolio and what you want to include in it. Also, look here later today for the poetic habits.

Tuesday, October 23, 2007

A prose poem about bird song

So, forget most of what I said about line:

Frailty, that rarely, like the thrush, the gorgeous song in us climbs, a bird ashamed of its arriving at a possession of beauty by unsanctioned means, a slouching off to such a dim-lit place where the song erupts in spite, its open-winged remembering, seining from the quiet—

from Of the Song Bird by Margo Berdeshevsky

Frailty, that rarely, like the thrush, the gorgeous song in us climbs, a bird ashamed of its arriving at a possession of beauty by unsanctioned means, a slouching off to such a dim-lit place where the song erupts in spite, its open-winged remembering, seining from the quiet—

from Of the Song Bird by Margo Berdeshevsky

Friday, October 19, 2007

More on Turner

Because several of my links didn't work in responding to Blade's good questions below, and because it might be a useful way to help think about deep context, and because I'm vain, here's a respost of my lengthy response from that earlier thread:

Blade—

Thanks for the comment on the Turner poem. A couple of things, one of which, at least, we talked about over lunch. The formatting of the version here is from the on-line journal where it was published. The space is meant, more or less, to mimic the bright strip of light down the painting’s middle.

In the interest of “deep context,” let me show you what a mess this kind of writing can lead to. Your question about “fanacious” was posed a number of years ago by a woman who was leading a discussion group on a web board. After searching through some very old emails (back when most of the folks in this class were not yet in high school--sigh) I found the exchange below, updated a bit to make links a bit more relevant.

She wrote: At my instigation, my online reading group has started a discussion of your poem, Before You Read the Plaque About Turner's 'Slave Ship.'" . . . we've all run aground on "fanacious." One of us discovered that it's in Turner's epigram to the painting, but we still have no clue as to its meaning.

I wrote back: When I included the Turner poem on my list for a humanities class, I did it because my students asked if I'd written about paintings. I had not expected too many others to visit the site. Still, I'm quite glad it found you (or you found it). I was, in fact, a bit surprised as I moved on from Richland this fall to take a teaching job here in the Chicago area.

In answer to your question: "fanacious" is a term stolen straight from Turner's epigraph to the painting. He attached to it these lines: "Hope, Hope, fanacious Hope!/Where is thy market now?" I included it for two reasons. 1) Because I wanted to slide Turner's own voice/sensibility into the conversation, somehow. 2) Because I loved the sound of that word, fanacious.

Like you, though, I couldn't figure out for the life of me what it meant--despite my best efforts to search dictionaries, including the OED. I guessed roughly what one of your group members suggested—a conflation of fanatical and tenacious. Still, I including the word because I loved its sound. I initially read about the epigraph from this very

helpful site, a web version of the work of Victorian scholar George Landow.

Since then, I've been asked a few times about it, and I've dug around enough to learn that the lines are purported to have been an altered quote from the 18th century writer James Thomson (turns out I wasn't getting Turner's voice into the poem after all). The entire quote was this:

(I picked this up from a site at the U of Texas which is no longer available on-line. The hard copy I have quotes a good deal from the work of John McCoubrey (as does Landow)).

So is the term fanacious or fallacious? I'm not certain. I AM certain that the power and foolishness of the "market" determining the fate of human lives is a kind of evil that the painting helps me to see, to imagine and include myself in, somehow.

Later, in response to an additional inquiry in the discussion group, I wrote:

With the risk of shutting down discussion on a another concern you raised, I use the term "master" at the end of the poem in a way that, I hope, suggests three possible connotations of the term, all of which have interesting resonances given the subject matter. There's the use of "master" in regards to slavery and the ship. The use of master to refer to the master painter of a masterpiece (who cannot light the depths, no matter how good he is at light-play about the surface) and, yes, the master God, whom Turner saw as punishing the perpetrators of this crime, yet, troublingly, who doesn't seem to save those very human bodies sinking down.

One final note about how deep context works. In reading about this painting, I also found John Ruskin’s lines about Turner’s work, and I included a few in the poem. Here’s a portion of the quote (Landow uses it to, in part, critique Ruskin’s gushing about Turner):

Purple and blue, the lurid shadows of the hollow breakers are cast upon the mist of night, which gathers cold and low, advancing like the shallow of death upon the guilty ship as it labours amidst the lightning of the sea, its thin masts written upon the sky in lines of blood, girded with condemnation in that fearful hue which signs the sky with horror, and mixes its flaming flood with the sunlight, and, cast far along the desolate heave of the sepulchral waves, incarnadines the multitudinous sea.

What’s important to me, though, as a writer, is how way leads on to way. I ended up getting fascinated with Ruskin and his idea of the pathetic fallacy. That ended up leading to another long poem, this one engaging Ruskin and nature and poetry, and all sorts of other false leads and deep contexts and whatnot.

Blade—

Thanks for the comment on the Turner poem. A couple of things, one of which, at least, we talked about over lunch. The formatting of the version here is from the on-line journal where it was published. The space is meant, more or less, to mimic the bright strip of light down the painting’s middle.

In the interest of “deep context,” let me show you what a mess this kind of writing can lead to. Your question about “fanacious” was posed a number of years ago by a woman who was leading a discussion group on a web board. After searching through some very old emails (back when most of the folks in this class were not yet in high school--sigh) I found the exchange below, updated a bit to make links a bit more relevant.

She wrote: At my instigation, my online reading group has started a discussion of your poem, Before You Read the Plaque About Turner's 'Slave Ship.'" . . . we've all run aground on "fanacious." One of us discovered that it's in Turner's epigram to the painting, but we still have no clue as to its meaning.

I wrote back: When I included the Turner poem on my list for a humanities class, I did it because my students asked if I'd written about paintings. I had not expected too many others to visit the site. Still, I'm quite glad it found you (or you found it). I was, in fact, a bit surprised as I moved on from Richland this fall to take a teaching job here in the Chicago area.

In answer to your question: "fanacious" is a term stolen straight from Turner's epigraph to the painting. He attached to it these lines: "Hope, Hope, fanacious Hope!/Where is thy market now?" I included it for two reasons. 1) Because I wanted to slide Turner's own voice/sensibility into the conversation, somehow. 2) Because I loved the sound of that word, fanacious.

Like you, though, I couldn't figure out for the life of me what it meant--despite my best efforts to search dictionaries, including the OED. I guessed roughly what one of your group members suggested—a conflation of fanatical and tenacious. Still, I including the word because I loved its sound. I initially read about the epigraph from this very

helpful site, a web version of the work of Victorian scholar George Landow.

Since then, I've been asked a few times about it, and I've dug around enough to learn that the lines are purported to have been an altered quote from the 18th century writer James Thomson (turns out I wasn't getting Turner's voice into the poem after all). The entire quote was this:

'Aloft all hands, strike the top-masts and belay;

Yon angry setting sun and fierce-edged clouds

Declare the Typhoon's coming.

Before it sweeps your decks, throw overboard

The dead and dying--ne'er heed their chains

Hope, Hope, fallacious Hope!

Where is thy market now?'

(I picked this up from a site at the U of Texas which is no longer available on-line. The hard copy I have quotes a good deal from the work of John McCoubrey (as does Landow)).

So is the term fanacious or fallacious? I'm not certain. I AM certain that the power and foolishness of the "market" determining the fate of human lives is a kind of evil that the painting helps me to see, to imagine and include myself in, somehow.

Later, in response to an additional inquiry in the discussion group, I wrote:

With the risk of shutting down discussion on a another concern you raised, I use the term "master" at the end of the poem in a way that, I hope, suggests three possible connotations of the term, all of which have interesting resonances given the subject matter. There's the use of "master" in regards to slavery and the ship. The use of master to refer to the master painter of a masterpiece (who cannot light the depths, no matter how good he is at light-play about the surface) and, yes, the master God, whom Turner saw as punishing the perpetrators of this crime, yet, troublingly, who doesn't seem to save those very human bodies sinking down.

One final note about how deep context works. In reading about this painting, I also found John Ruskin’s lines about Turner’s work, and I included a few in the poem. Here’s a portion of the quote (Landow uses it to, in part, critique Ruskin’s gushing about Turner):

Purple and blue, the lurid shadows of the hollow breakers are cast upon the mist of night, which gathers cold and low, advancing like the shallow of death upon the guilty ship as it labours amidst the lightning of the sea, its thin masts written upon the sky in lines of blood, girded with condemnation in that fearful hue which signs the sky with horror, and mixes its flaming flood with the sunlight, and, cast far along the desolate heave of the sepulchral waves, incarnadines the multitudinous sea.

What’s important to me, though, as a writer, is how way leads on to way. I ended up getting fascinated with Ruskin and his idea of the pathetic fallacy. That ended up leading to another long poem, this one engaging Ruskin and nature and poetry, and all sorts of other false leads and deep contexts and whatnot.

Labels:

Blade B.,

D. Wright,

deep context,

J. M. W. Turner,

Ruskin

More Poetics