Tuesday, March 15, 2011

Wednesday, December 1, 2010

All problems can be solved musically--Dean Young

"All problems can be solved musically. On one of those umpteen Miles Davis box sets, there are three takes of a single song: in the first Coltrane hits an obviously off note, a clam it’s called in the recording industry, in the second he hits it again, at a different point, augments it, chooses it, this is Coltrane, man, so by the third time it’s not a wrong note, it’s an integral part of his solo . . . Life my friends is a mess. Mistakes aren’t contaminants any more than conception is infection. Fucked up before I got here, fucked up while I hung around, fucked up when I’m gone. Good news!" (154)

Monday, November 8, 2010

Second Installment--Musical Ekphrasis

I want to pick up on a number of things tonight, trying to address a few of the questions and concerns folks raised. First, let me remind you of the several kinds of musical ekphrasis I identified, only the first of which I posted on. I wrote:

I see modern/contemporary poets responding to music in these four or five ways:

1) memorial/commemorative (music as invocation of particular individual experiences)

2) contextual icon (poems exploring music as cultural/biographical/historical means into a composer’s life, an era, etc.)

3) mimetic/echoing (poems that imitate and seek the physical/sonic/emotional effects of music)

4) music as figure/god/form (poems that identify music as an idealized form of making art/meaning or as a version of mystery/power beyond language)

5) the riff (music that improvises and dialogues with music, drawing together many or most of the notions above in a single place)

So my mentor for the semester said this in response to my post:

I've always equated ekphrasis with writing about a particular painting or drawing or photo. I'm thinking about William Carlos William's "Landscape with the Fall of Icarus." So I was surprised that these poems all seemed to be about a personal experience that the speakers had with music: the mother playing the piano, the kid singing to the juke boxetc. They weren't responses to music so much as memories of events and people connected to music. Would you agree?

Here's how I would/did respond:

Absolutely I agree.* In these poems music is a springboard, often even particular pieces of music or particular singers/composers/etc. for the epiphanic, memorial lyric. At one point I was going to write something like this to talk about how such poems, as much as I love them, often ignore the actual experience of music:

At my age, nearly every one I know has a dead grandma with a favorite hymn. Or an involuntary moment of sexual arousal upon hearing the first five notes of an album he made out to in high school. Or can still sit down at the piano or pick up a guitar and play the first song she learned. Or sustains a perverse love for a marginal pop hit to which we made up alternative/obscene lyrics to be sung in the car (lyrics which have since completely erased all memory of the original words). And almost every poet I know (these are quite often the very same people) has a set of poems about the hymn to which his dead grandma made out in high school while her boyfriend played the guitar and made up alternate lyrics.

But of course I realize that for most of us memory and music are so inextricable (see this amazing study) that it would be impossible to shut off poems about music from such associative connections. And why would you want to, completely?

Still, I find these poems limited precisely because there is so, so much about music they really do not take into account, so let me skip number two in my list and move on to number three:

3) mimetic/echoing (poems that imitate and seek the physical/sonic/emotional effects of music)

Of course I have a long, long discourse on this in my essay, but I want to point out just two poems.

First, Langston Hughes, who was one of the first to attempt to tranlate the experience of the blues (the music, not the emotion) into modern poetry. What some scholars have noted about this process, is how Hughes’ attempts developed over time from, at first simply transcribing or mimicking blues lyrics and rhythms. But readers/scholars almost universally agree “[t]hat Hughes writes his best blues poetry when he tries least to imitate the folk blues is a critical commonplace” (Chinitz 179). While David Chinitz (one of my former profs at Loyola University in Chicago) challenges this common wisdom, I still the basic insight it instructive. The musical ekphrastic poem is an engagement with the music.  Rather than a mere transcription of the blues, or an attempt to write lyrics to be sung, blues poetry follows Langston Hughes' struggle to capture "the quality of genuine blues in performance while remaining effective as poems" (Chinitz 177). For Hughes and the many writers who merge into and out of the tradition (see some attached suggestions below) the central challenges have been "First, how to write blues poems in such a way the they work on the printed page, and second, how to exploit the blues form poetically without losing all sense of authenticity" (177).

Rather than a mere transcription of the blues, or an attempt to write lyrics to be sung, blues poetry follows Langston Hughes' struggle to capture "the quality of genuine blues in performance while remaining effective as poems" (Chinitz 177). For Hughes and the many writers who merge into and out of the tradition (see some attached suggestions below) the central challenges have been "First, how to write blues poems in such a way the they work on the printed page, and second, how to exploit the blues form poetically without losing all sense of authenticity" (177).

So to see how Hughes works through/past that challenge, we can take a look at his most famous blues poem, The Weary Blues and see how he combines several impulses to generate a kind of musical experience that adds to or supplements the blues. He gives us a narrative and a character that frames the several quotations from an actual blues tune. The rhyme, repeated lines, and quotations combine to feel like the blues, even though they are not all strictly blues forms. But then other poetic devices, like alliteration, assonance, caesuras also do things poetry can do that an actual blues singer cannot.

So as you write, or try to write a poem about music, what poetic tools can you bring to the poem that do something in addition to describing or transcribing a musical encounter?

Second, some poets adopt new formalist techniques to give a musical texture to their poems, reaching back into the deeper connections between music and poetry. A. E. Stallings has done this often, most notably I think in Blackbird Etude where her small stanzas (rhymed haikus with their 5, 7, 5 syllabics), her enjambed rhyme, and her sonic play with unexpected diction (“melismatic runs sur-/passing earthbound skills”) give music-like shape to the blackbird’s song. She shapes a wild creatures song with poetic forms and reference in the title to an etude, that most classical sort of music pedagogy.

Myself, I love the pantoum as a musical form, one that allows me to make music while at the same time not merely imitating (I hope). Here’s a pantoum from a number of years back responding to a performance by Ella Fitzgerald near the end of her life, an experience at the time I had no idea was so remarkable.

If you want to try and write a musical poem, two considerations I would make. What is the form of the piece of music, at least as you understand it. Can you use that as at least a shape to your poem? For instance, a poem about a sonata might be a four or five part poem, loosely following the music form. Even though you cannot reproduce the exact tones, rhythms, etc. of the sonata, you could rely on its shape to “inform” your own poem.

Second, I always try to think not just of the music’s formal qualities, but also the form of my experience of the music. For instance, Hughes' narrative and cultural explorations in "The Weary Blues" are central to the poem. Or in my Ella poem, I am thinking of how my mind wandered from her frailty to the qualities of the music, to the associations I have with other jazz musicians when I think of her, to the connotative possiblities of words like "trip."

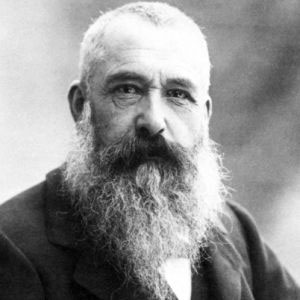

*Though I would work with a more expansive definition of ekphrasis than those poems that  write about only a single work of art. I think one of the best, and an example of visual ekphrasis that falls into my second category above, is Lisel Mueller's Monet Refuses the Operation which refers to a whole list of Monet’s works, using the painter’s voice to describe and examine them (and lift them off the page).

write about only a single work of art. I think one of the best, and an example of visual ekphrasis that falls into my second category above, is Lisel Mueller's Monet Refuses the Operation which refers to a whole list of Monet’s works, using the painter’s voice to describe and examine them (and lift them off the page).

Here's the formal bib reference to David Chinitz's article:

Literacy and Authenticity: the Blues Poems of Langston Hughes." Callaloo 19 (1996): 177-92.

Tuesday, November 2, 2010

Four Anthologies of Musical Ekphrasis

Music Lover's Poetry Anthology, ed. by Helen Hardy Houghton and Maureen McCarthy Draper

Music's Spell: Poems about Music and Musicians, ed. by Emily Fragos

Jazz Poems, ed. by Kevin Young

Blues Poems, ed. by Kevin Young

Monday, November 1, 2010

Discussion One on Musical Ekphrasis

For the graduate school essay I mention below, I am posting a series of classroom discussions on various ways poets respond to music. Here's the first day's discussion.

For the graduate school essay I mention below, I am posting a series of classroom discussions on various ways poets respond to music. Here's the first day's discussion.“Writing about music,” says Elvis Costello (or Steve Martin, Thelonius Monk, Laurie Anderson, Martin Mull, Frank Zappa, etc.) “is like dancing about architecture. It’s a stupid thing to want to do.” This hasn’t stopped me (or most of the poets I regularly read) from writing dozens of poems about music—music as source of inspiration, font of memory, ideal of form, or subject of artistic envy. Then again, I am also someone who was once spotted dancing on a hill near a Frank Lloyd Wright hotel in southwestern Wisconsin)

My essay explores the dynamics of “musical ekphrasis.” If you want a formal preview, you can read the abstract, or you can refer to the “map” of the essay above.

Here, though, is some material for us to discuss on how poets write in response to music and musical experience.

First a few caveats, definitions, and misdirections:

1) What I am NOT writing about—the shared lineage of music and poetry (I too believe that all the ancient poets were bards who sang their epics and their lyrics on honeyed tongues to the listening masses—but that’s not what I am studying—and besides that hasn’t been the case for say, oh, about a thousand years). Also, I’m not writing about whether or not lyrics (popular or otherwise) qualify as poetry (a subject on which I have many strong, well-informed opinions, none of which matter in this essay—short answer, “usually not”). Also, though I am interested in the notion, I am not writing about how musicians respond to works of visual art (which is what this scholar has done).

3) Though ekphrasis has its origins in ancient Greek rhetoric, I’m talking here primarily about the poetic tradition that picked up steam in the early 19th century with work by the Romantics who frequently depicted encounters with visual art as nearly sacramental (in ways often replacing more formal religious encounters and challenged only by direct encounters with nature). Of course the great example of this is John Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn." And then there are countless 20th century examples of ekphrasis, the modernists Stevens, Williams, Stein, Auden and since.

4) Of course you can read Keats’ “Ode” as not only an essential/founding example of ekphrasis but also as an emblematic poem of musical ekphrasis—the relationship between silence, music, imagination, and poetry. Melodies, pipes, timbrels, song occupy nearly as much space in the poem as anything else. And so I want to make a case that musical ekphrasis can be seen as an equally important category of poetry, especially in modern and contemporary poetry.

5) In truth, though, I don’t really want to “make a case” for anything (that’s why I gave up on my dissertation and turned to making my own poems instead). I would rather explore HOW poets respond poetically to music and suggest how this has been valuable to my own reading, writing and teaching of poetry and how it might prove valuable and generative to the work of other writers and readers. I’m also interested in this with visual ekphrasis, which explains why I have taught courses in both subjects and used to keep an ongoing blog on the subject. Plus, Lauren Rusk already wrote a very strong piece for the AWP Chronicle a few years back on “The Perils and Possibilities of Writing about Visual Art.” At the end of the week, I will put up a prompt, some suggestions, and some warnings for writing musical ekphrasis, stuff I hope you all might find generative of new work.

MUSICAL EKPHRASIS

The contemporary practice (1920s through yesterday) of musical ekphrasis takes on a thousand varieties of form and approaches, but at the core I am interested in those poems that struggle to improvise a space that is itself an experience (in and through language) of a felt knowledge, a resonant intimacy, and an embodied/shared sonic experience generated primarily by an encounter with music.

I see modern/contemporary poets responding to music in these four or five ways:

1) memorial/commemorative (music as invocation of particular individual experiences)

2) contextual icon (poems exploring music as cultural/biographical/historical means into a composer’s life, an era, etc.)

3) mimetic/echoing (poems that imitate and seek the physical/sonic/emotional effects of music)

4) music as figure/god/form (poems that identify music as an idealized form of making art/meaning or as a version of mystery/power beyond language)

5) the riff (poetry that improvises and dialogues with music, drawing together many or most of the notions above in a single place)

So each day this week, I am going to put forward a poem or two that stand inside one of these categories and ask for your response.

Memorial/Commemorative Musical Ekphrasis

Here are a number of poems that attempt to give “an account of an unforgettable moment” that is tied directly to music, to show “how music has shown us to ourselves more accurately, and given us as well the eerie means to understand transcendence—to step back out of our lives and look back at them” (McClatchy xv).

If you would, pick one of the poems and discuss how it marries/connects music with memory.

How does the poem celebrate, lament, question, reject the musical experience?

And what craft choices does the writer use to represent the music itself?

Which piece of music in your experience immediately evokes powerful memories for you? Have you written about this piece?

Or, alternately, do you have a suggestion of a poem that connects music and memory? I’d love to see it.

Edna St. Vincent Millay, “On Hearing a Symphony of Beethoven”

Frank O'Hara "The Day Lady Died" (Here is Billie Holiday singing "God Bless the Child")

Linda Pastan, “Practicing”

Dorianne Laux, "The Ebony Chickering"Denis Johnson, “Heat”

Wendell Berry, “A Music”

Naomi Shihab Nye, “Hugging the Jukebox”

Kevin Stein, “First Performance of the Rock ‘n’ Roll Band Puce Exit”

Abstract of an Essay in Progress

As part of a graduate MFA course, I am trying to tame a paper on Musical Ekphrasis. Above is what it looks like when I work on such things. Here is the abstract of the essay.

Ekphrasis--the practice of writing poems in response to visual art--occupies a prominent place in modern and contemporary American poetry (though it dates back centuries, gaining special esteem during the era of Romanticism). Drawing on this deep ekphrastic tradition, this essay proposes "musical ekphrasis" as an equally valuable way to consider and generate contemporary poems. Musical ekphrastics are poems that represent, respond to, and engage sensuously with musical experience. Langston Hughes, Frank O'Hara, Lisel Mueller, Jean Janzen, Terrance Hayes, and others write poems that grow from various encounters with music, often experimenting with formal innovation and deeply embodied imagery. The poets engage musical experience in memorial, figurative, contextualized, lyrical ways that can be understood as relating to ekphrasis. However, the poems also have their own unique mean of poetic knowing, a way best understood in terms of improvisation between writers, musicians and readers. Practical considerations for how poets might attend to music in a generative fashion conclude the essay.

Tuesday, November 11, 2008

A Music--Wendell Berry

in the the tunnel of the Mètro. I pay him

a coin as hard as his notes,

and maybe he has employed me, and pays me

with his playing to hear him play.

Maybe we're necessary to each other,

and this vacant place has need of us both

––it's vacant, I mean, of dwellers,

is populated by passages and absences.

By some fate or knack he has chosen

to place his music in this cavity

where there's nothing to look at

and blindness costs him nothing.

Nothing was here before he came.

His music goes out among the sounds

of footsteps passing. The tunnel is the resonance

and meaning of what he plays.

It's his music, not the place, I go by.

In this light which is just a fact, like darkness

or the edge or end of what you may be

going toward, he turns his cap up on his knees

and leaves it there to ask and wait, and holds up

his mandolin, the lantern of his world;

his fingers make their pattern on the wires.

This is not the pursuing of rhythm

of a blind cane pecking in the sun,

but is a singing in a dark place.

Saturday, August 9, 2008

On 52nd Street--Philip Levine

the Deuces silenced, the lights

lowered, and breath gathered

for the coming storm. Then nothing,

not a single note. Outside starlight

from heaven fell unseen, a quarter-

moon, promised, was no show,

ditto the rain. Late August of '50,

NYC, the long summer of abundance

and our new war. In the mirror behind

the bar, the spirits--imitating you--

stared at themselves. At the bar

the tenor player up from Philly, shut

his eyes and whispered to no one,

"Same thing last night." Everyone

been coming all week long

to hear this. The big brown bass

sighed and slumped against

the piano, the cymbals held

their dry cheeks and stopped

chicking and chucking. You went

back to drinking and ignored

the unignorable. When the door

swung open it was Pettiford

in work clothes, midnight suit,

starched shirt, narrow black tie,

spit shined shoes, as ready

as he'd ever be. Eyebrows

raised, the Irish bartender

shook his head, so Pettiford eased

himself down at an empty table,

closed up his Herald Tribune,

and shook his head. Did the TV

come on, did the jukebox bring us

Dinah Washington, did the stars

keep their appointments, did the moon

show, quartered or full, sprinkling

its soft light down? The night's

still there, just where it was, just

where it'll always be without

its music. You're still there too

holding your breath. Bud walked out.

Wednesday, June 11, 2008

Two Violins--A. E. Stallings

An A. E. Stallings poem from the June issue of Poetry. I like the penultimate stanza:

One was fire red,

Hand carved and new—

The local maker pried the wood

From a torn-down church's pew,

The Devil's instrument

Wrenched from the house of God.

It answered merrily and clear

Though my fingering was flawed;

Bright and sharp as a young wine,

They said, but it would mellow,

And that I would grow into it.

The other one was yellow

And nicked down at the chin,

A varnish of Baltic amber,

A one-piece back of tiger maple

And a low, dark timbre.

A century old, they said,

Its sound will never change.

Rich and deep on G and D,

Thin on the upper range,

And how it came from the Old World

Was anybody's guess—

Light as an exile's suitcase,

A belly of emptiness:

That was the one I chose

(Not the one of flame)

And teachers would turn in their practiced hands

To see whence the sad notes came.

Thursday, May 22, 2008

Musical Excurstion--Part Three*

Option Three: Attend a live performance, rehearsal or ritual use of music (a worship service or patriotic gathering, for instance). In addition to listening closely to the music, pay attention to what you observe and what you experience in your body.

Attend to the way the musicians (which might include you) move and use their bodies to produce sound (fingers, breath, muscles). Notice also their emotional reactions and facial expressions. How do their “feelings” translate into sound? Observe how various musicians work together, or how a solo performer engages or ignores her audience. What about this social experience of music makes it differ from listening to a recording? To what uses is this music put (is it an escape, a source of connection, background music, a didactic force)? How does the “utility” of the music affect your sense of its artistic value? Describe as well the physical space in which you encounter this music. In what ways do the walls, the floors, the benches affect the sound and sense of the music?

Attend to the way the musicians (which might include you) move and use their bodies to produce sound (fingers, breath, muscles). Notice also their emotional reactions and facial expressions. How do their “feelings” translate into sound? Observe how various musicians work together, or how a solo performer engages or ignores her audience. What about this social experience of music makes it differ from listening to a recording? To what uses is this music put (is it an escape, a source of connection, background music, a didactic force)? How does the “utility” of the music affect your sense of its artistic value? Describe as well the physical space in which you encounter this music. In what ways do the walls, the floors, the benches affect the sound and sense of the music? After you’ve left the venue, either right away of some time later, try to recall the experience in as vivid detail as you can, focusing especially on the music you remember. Which musical quality stays with you? And which non-musical detail remains?

Deep(er) Contexts(and how they might find their way into your writing about music)

1) With a bit of research, identify the narrative elements you would need to know in order to better understand a musical work—setting, character, point of view, conflict(s). If it’s a love song or an oratorio, what’s the story that structures the piece? What moment in the biblical or mythical or historical record is being portrayed? What elements of that narrative are left out? Which characters disappear and which are emphasized? Who is “telling” this part of the tale? Consider “finishing” or “unfinishing” the story with your work.

1) With a bit of research, identify the narrative elements you would need to know in order to better understand a musical work—setting, character, point of view, conflict(s). If it’s a love song or an oratorio, what’s the story that structures the piece? What moment in the biblical or mythical or historical record is being portrayed? What elements of that narrative are left out? Which characters disappear and which are emphasized? Who is “telling” this part of the tale? Consider “finishing” or “unfinishing” the story with your work. 2) What kinds of cultural conflict or personal upheaval pervaded the artist’s world when the work was made or performed—a war, death of a beloved, divorce, illness, moment of cultural excitement, etc.? How are these events present in the work, implicitly or explicitly? Or how does the work move away from these conflicts, masking them, or using the music as a sanctuary? Is the work in protest to the situation? Is the work about coming to peace with its surroundings? By knowing the conflicted situation within which the work emerged, how do you feel closeness or distance from its work?

3) In contrast to chaos and conflict, investigate the typical habits, manners, and patterns that might have been part of the work’s emergence (or the lives it represents). What work was done as this song was sung? Who has made love with the music in the background? Where does this Bach chorale come in a typical Lutheran service? How might the work itself or the objects to which it refers have had daily, practical uses in the lives of people? What do these details add to the structure or pattern of your poem, story or essay? How do they change your sense of the work to which you’re attending?

4) Biographical context, especially the way a particular work either represents a period of an artist’s life or affects his or her life, is unavoidably attractive. Read a biography of the performer or composer and see if the work you’re listening to has been mentioned. How did the creator of that work view it? What might the artist have said or done just before the work was made? What obvious or hidden impetus led to the work? How did she feel once it had been completed? What did he claim to intend that is missing or (indeed) present? What effect did this work have on his reputation? Where did she rank the work in relation to other pieces? If this piece is highly popular, how might the artist feel about it now? What technical problem did the artist work out in completing this sonata or symphony?

5) Find one or two primary sources, such as diaries, artistic statements, interviews, photographs, films that can be woven into your poem or prose, either implicitly or explicitly. Consider using a quotation from one of these sources for an epigraph or as a concluding line. Consider arguing with the artist’s words directly, using the music as evidence against him or her.

6) Investigate the artistic movements/trends/techniques that your work uses and to which it responds. To what other artists was this composer paying close attention? With what contemporaries (or traditional masters) is this composer or performer conversing? What does he steal? What does she alter? How does the work represent a movement or school of art or music? Find the movement’s founding statements and consider them as part of your poem.

7) What kind of critical and/or popular reception has this work enjoyed? How has this reception changed over time? Where in this procession of responses is your own reaction? Is the work popular or obscure? Who knows about it and what uses do these audiences make of the song (for instance, in what weird commercial would you see or hear this piece)? Can you use some of the critical comments as language for your work? Can you make the audience/critics characters in your fiction or poem?

8) Consider the song as an object/artifact (think of the film “The Red Violin”). Who has owned the vinyl record or the sheet music? Where has it been sold? What near losses has it survived? How many times has the song been performed? What marks have those encounters left on the work? What changes have occurred in its uses (for instance, going from ritual use to concert performance)? How might the earliest performers of a tune think of its current use? How do you know?

9) When I learned that the sarabande was a dance, it changed my entire sense of Bach’s first Unaccompanied Suite for Cello, demonstrating the power of terms to affect what we hear. That sense changed even more when I realized it was a dance that had been banned for its suggestiveness. Investigate one or two of the musical terms that apply to your piece of music. What difference does it make to you to understand the structure of 12-bar blues or to know the difference between andante and allegro? How would you contrast the official definition of a musical device with your actual experience of the piece?

Writing the Song

Poetry offers a very strong way to give a verbal representation of sonic and rhythmic experience, emphasizing in language an embodied encounter with a piece of music. A range of formal choices can follow from your response to the piece. If you note repetitions, you might consider a formal poem that can offer its own sonic pattern of repetition (a pantoum, a villanelle, or a sestina, perhaps, or a use of anaphora or rhyme). You might offer alliteration, assonance of internal rhyme as ways of heightening the musical qualities of language. Or you might be attentive to metrical variations and caesuras.

In your fiction you might highlight the memorial functions of a song. Consider how various artists, styles or tunes offer good ways to invoke setting—era, culture, etc. Explore the ways various characters use music as a way or marking their lives, as a kind of unofficial soundtrack of experience. Or explore a ritualized experience for your characters and its connection to song (the way a hymn suggests home, or the function of lullaby as it passes from one generation to the next). How can you create entire scenes around a particular musical instance—teaching, learning, hearing a song? What social exchanges require music (think here of the role of dance in Jane Austen’s or Edith Wharton’s novels)?

Non-Fiction offers many ways to examine the effects of music on individuals and communities, as well as to examine the difficulties in communicating musical experience to others. Focus on a particular element of you own growth in musical awareness and try to describe how it happened. What did it take for you to collect all of the vinyl versions of a particular artist’s work, and why do you value them over others? Or what happened when you stopped practicing the piano, as your parents wanted, and then picked up the guitar or gave up music in favor of driving your car downtown looking for girls/guys? What did it mean when you formed or broke up with a band? How do you miss or embrace singing hymns or being part of a choice? Or what has music meant to you in especially difficult or joyous times, and how has that changed over the years?

*This is part two of an exercise I'm drafting for this course. Again, please post poems or send responses to this excursion. You'll note that, again, that this excursion opens itself to the possibility of poetry, fiction, or non-fiction. For the Poetry, Poetics, and the Arts Class, only the poetry options will be open.

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

Musical Excursion--Part Two*

Option Two: Choose a recording of an unfamiliar piece of music, perhaps something utterly beyond your usual musical habits and tastes, or perhaps an obscure tune by your favorite singer, one you haven’t heard in years. As you listen to the music, what do you notice about the piece or about your physical/emotional reaction to it? Are you moved or bored? Do you feel critical or full of praise? What surprises you about the music? What seems predictable? When the piece finishes, what remains in your head—phrase, melody, feeling? Finally, probe each of your responses and see if you can connect a concrete image or physical sensation with each one. For instance, “When the djembe plays, the thud of the hand on the head of the drum resonates like a foot stomping on the floor ” or “Dylan’s voice made my teeth grind.”

During a second listen, notice what you missed the first time. How has your initial response changed or been confirmed? What new questions does the second encounter raise for you? What additional information, about the composer, about the uses of the music, or about its musical/formal qualities would you like to know?

Finally, if possible, find an additional recording of the song. How is this performance different from the one you heard initially? What aspects remain constant? Which do you enjoy more, and why? Which recording would you recommend to someone else?

Write a paragraph or poem that either a) contrasts or layers the experience of hearing the two recordings on top of one another; or b) describes your reactions to the newness or surprise of the piece and/or lays out the questions you’d like to answer for yourself after listening to this new music. Or develop a character sketch of the performer you have heard, or the composer of the piece, investigating the significance of this tune in his life.

Write a paragraph or poem that either a) contrasts or layers the experience of hearing the two recordings on top of one another; or b) describes your reactions to the newness or surprise of the piece and/or lays out the questions you’d like to answer for yourself after listening to this new music. Or develop a character sketch of the performer you have heard, or the composer of the piece, investigating the significance of this tune in his life.*This is part two of an exercise I'm drafting for this course. Option three will appear tomorrow, with other aspects of the excursion to follow. Again, I'm interested in reading responses to this excursion. You'll note that, in this version, the excursion opens itself to the possibility of poetry, fiction, or non-fiction. For the Poetry, Poetics, and the Arts Class, only the poetry options will be open.

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

A Musical Excursion*

As I type this, music pours through my headphones, a Bach suite for unaccompanied cello, recorded by the great Pablo Casals in the middle of the last century. Hearing Casals play on my iPod, I can’t help but think of the time I heard this same piece played by Slovakian cellist Josef Luptak. While sitting on wooden pews in a stone chapel in an Austrian castle, as Josef reached the end of the sarabande, we saw mist settle on mountains just barely visible from the tiny arched window.

As I type this, music pours through my headphones, a Bach suite for unaccompanied cello, recorded by the great Pablo Casals in the middle of the last century. Hearing Casals play on my iPod, I can’t help but think of the time I heard this same piece played by Slovakian cellist Josef Luptak. While sitting on wooden pews in a stone chapel in an Austrian castle, as Josef reached the end of the sarabande, we saw mist settle on mountains just barely visible from the tiny arched window. And, almost as a miracle, in the silent space between movements, birds sang. Everyone was still. For a moment we inhabited together a sacred space made possible by Bach, by Luptak, by his listeners, by the setting, and, wonderfully, by some random, improvisatory birds. How I’ve wondered (for five years or more), do I write this? Should it be written?

And, almost as a miracle, in the silent space between movements, birds sang. Everyone was still. For a moment we inhabited together a sacred space made possible by Bach, by Luptak, by his listeners, by the setting, and, wonderfully, by some random, improvisatory birds. How I’ve wondered (for five years or more), do I write this? Should it be written? While nearly everyone has some kind of powerful experience with music—hearing, performing, practicing,

dancing—we often have difficulty expressing music’s effects, its means of moving, comforting, or energizing us.

Descriptions often seem either cold and technical or florid and vague. In both deliberate and serendipitous ways, this

excursion encourages us to find in our musical encounters generative energy for poems, stories, and reflective prose,

to engage our bodies, memories, and intelligence in ways that might hint at the deep connections between language

and music, between story and memory as it appears in song.

Embodied Listening

Begin this excursion with one of these three exercises, each designed to generate a draft that can be focused or

expanded by responding to the questions below.

Option One: Choose a recording of a very familiar piece of music, one you’ve listened to, sung, or played countless

times. As you listen to the song, make a list of all the associations you have with the piece. When/how did it come

into your life? When do you catch yourself humming it? What do you think of the composer/performer? With whom

have you shared your appreciation for this song? What other songs/artists make music like this? Once you’ve made

your list, set it aside and listen to the song again.

This time try to forget your past associations with the music and attend instead to your body’s response to the

music. Do your muscles feel relaxed or tense? What happens to your breathing? Have you shut your eyes or left them

open? As the sound fills your head, how do you react? Does your heartbeat quicken or slow down? Do you dance, or

tap your toes, or play the drums with your pencil? As soon as the music ends, close your eyes and sit with these

physical sensations for a few moments (as long as you are able). When you open your eyes, what sensations remain?

Set your two lists side by side and listen a third time. What aspect of the music itself—tempo, lyrics, rhythm,

repetitions, variations, instrumentation, etc.—seems to connect the two lists you’ve made? What questions about the

performer or the composer arise for you? Not referring to your memorial associations or you own bodily experiences,

how would you describe this piece to someone who has never heard it? Would you put it in a genre? Would you

prescribe uses for it (perfect for a romantic evening, great to work out to, the best commuting tune, etc)?

Now, write three short poems (6-10 lines each), or three paragraphs (from a first person point of view), each

drawing from one of your lists. What theme, character, emotion, or experience begins to cohere from these three

pieces?

*This is part one of an exercise I'm drafting for this course when I teach it again in the fall. Options two and three will come tomorrow, with other aspects of the excursion to follow. I'd be interested in reading responses to this excursion. You'll note that, in this version, the excursion opens itself to the possibility of poetry, fiction, or non-fiction. For the Poetry, Poetics, and the Arts Class, only the poetry options will be open.

dw

Thursday, April 24, 2008

Day 24--Four Forms for Addressing the Tired Eye

1) First (person)

I am sick of seeing, tired of my eye,

of its clouds and precisions.

So I sit on purpose in the dark on my back porch and listen

to a woman I have never met play a violin.

I have come outside to enter my skin, to be blessed

in my skin by the lightest wind of April.

If I opened my eyes, I could see the violinist in her apartment,

the light behind her ponytail, the sway in her hip, her music stand.

But I prefer tonight her sound, her repetitions of the same raw

passage, a run in a movement of Brahms or someone like him.

All day long I have looked at paintings, at women, at men,

at books, at plates full of food. All night long I have remembered,

put them together in ways that require fine stitches. I know this

sounds like a poem. I know how to make my tongue turn

a word around so many ways it feels like a thing. So I am grown

sick as well of my mouth. But my ear so full

of the student’s song, and the air filled as well with her practice,

and my arms in the breeze, and my ass on this chair

matter as if I were, myself, a word, as if I were, tonight,

a sight for sore eyes.

2) Second (person)

If you opened your eyes, you could see me here in my apartment,

the light behind my head, the score on my music stand.

How does it sound, these repetitions of the same few measures?

Do you know the music of Edward Elgar, how it can feel,

at times, like Brahms, at times, like a world? All day long

I have practiced this passage in my mind.

All night long I have worked until it sounds, almost, like a poem.

Do you know how to make your ear turn a single pitch around

so many ways it feels like a word?

Are you in love with what I can do with my hands

on the bow and the strings?

My open window might seem an invitation. I am sorry.

What should I make of your heavy head tilted back in the dark?

From here, I have been watching you breathe while I practice.

From here what can be seen is clear enough. It could nearly be day.

3) First Persons (plural)

We have grown sick of seeing, tired of our eyes.

So we sit together in the dark on our porch and listen

to a woman practice a violin.

Could we have stayed inside in the light and still entered

our skin, alive like this in the lightest winds of April?

If we opened our eyes, we could see her apartment,

could see one another watching her in the dark.

We both say for a moment that we believe this music

is Brahms, a Concerto we heard once in Chicago.

We both know what we do with our days, how to take a body

or a term and turn it a few hundred ways

until it feels no longer like a thing. Are we in love

with all we do with our hands?

4) Imperative (didaction)

Go out in the dark and close your eyes for once.

Sit on purpose in the night on a back porch and listen

for someone you have never met, or imagine her

as she plays a violin. Enter your skin. Let it be blessed

by the lightest winds of April and her song.

Tuesday, April 22, 2008

Day 22--One of Several Hymn Riffs

“Jesus is fairer, Jesus is purer

who makes the wounded heart to sing.”

--Schönster Herr Jesu!

Every severed but still beating muscle,

each incised or punctured chamber—

We know these sorts of hearts,

the central, bursting metaphor

grown tender, corroded with age.

The dead have lived through an uneven

song, a vicious singing that tears

pulses from the signature of time,

from habits so far from pure.

Every heart we have is blemished

by the everyday beating we take

and give to ourselves. What other

kind of figure but the heart

would need to be made, to be wounded,

to ache its way through its own

hard, clotted hymn?

Thursday, April 10, 2008

Day 10: 1970s Arena Rock Love

She had a voice

like Peter Frampton’s guitar,

And a voice like Peter’s guitar could fill

a boy's skinny chest with wah wah & blues.

So, Peter, holding her like your guitar

that night in the empty high school gym

I lifted her delicate neck

and whispered “Show me the way”

And sang to her about how hard

it is to love anyone

When no one applauds or lifts

a lighter to the sky.

Sunday, April 6, 2008

Day 7-Call me Bonham

though the book bore

nothing on the title,

or the sticks broken,

or whipped away

while the band walked

off stage as he beat bare

hands bloody, and, maybe

a little drunk, he rocked

one foot on the treadle.

To make a mighty hook

you play a mighty lick

leave a damning wake,

and a broken stick,

and a riff, or two, behind.

Here's a much shortened version of John Bonham's drum solo from Led Zeppelin's "Moby Dick." Legend has it, he sometimes played for 30 mins or more.

Friday, April 4, 2008

Day 5--Fairy Tale

You are singing Stardust

like you’re Ella Fitzgerald,

and I am singing Stardust

dead on as Willie Nelson.

Together we have filled

our bedroom with enough

dust to set off your asthma,

though I think you’re scatting

when you cough in that syncopated

way that sounds like the earliest

records of the tune, before anyone

had written a single lyric.

And when I twine Willie’s smooth

near whine around you,

my eyes closed, imagined bandana

tight around my forehead,

you nearly die from the reverie,

the memory of the time

you nearly died running home

from school, the Wahlberg boy

chasing you. And here is Hoagy Carmichael

trying to strangle you now

with a few changes and a pulverized star.

I finish in time to pry

his hands from your neck.

We catch your breath

together and close our mouths

to the lovely and deadly dust

so plentiful in the near-light of dusk,

not purple, but dark blue and so plain.

Thursday, April 3, 2008

Day 4--Minor Resolution (or Stephen Isserlis Plays the Song of the Birds after the World Explodes)

Not only the small birds but the great, ungrounded

eagle, her slow curve from height, her slow curve

from depths again. I am not a believer in birds of war

but in this lark of the finger on string, in a g-minor wind become hymn.

Note: A lovely translation by Lydia Davis of the original song, along with commentary, from Poetry

Wednesday, March 12, 2008

Echo, after Palestrina

A voice in a high granite room

can sing a chord with itself,

can be its own deep, broad brother

of sound. Together by accident,

intent, it doesn’t matter.

Here alone with a radio,

I am not alone with a radio.

I am a full, full, resonant room.

dw

First appeared in Teaching English in the Two-Year College.

Monday, March 10, 2008

On Hearing a Symphony of Beethoven--Edna St. Vincent Millay

Sweet sounds, oh, beautiful music, do not cease!

Reject me not into the world again.

With you alone is excellence and peace,

Mankind made plausible, his purpose plain.

Enchanted in your air benign and shrewd,

With limbs a-sprawl and empty faces pale,

The spiteful and the stingy and the rude

Sleep like the scullions in the fairy-tale.

This moment is the best the world can give:

The tranquil blossom on the tortured stem.

Reject me not, sweet sounds; oh, let me live,

Till Doom espy my towers and scatter them,

A city spell-bound under the aging sun.

Music my rampart, and my only one.

For more of Millay's poetry