One of the assignments for the end of the semester portfolio involves writing 3-4 poems on a single "subject." By single subject, I mean a series of pieces that look at the same piece of art, the same song, the same composer, or the same artist. (Notice, also, that I've reduced the required number of pieces to a minimum of 3).

You may want to take a different approach to a poem you've already composed. You may want to write several new pieces. We'll discuss your approach at your portfolio conference, but you'll want to already have some ideas in mind for class on Tuesday.

You may want to take a different approach to a poem you've already composed. You may want to write several new pieces. We'll discuss your approach at your portfolio conference, but you'll want to already have some ideas in mind for class on Tuesday.To ready ourselves for this assignment, we'll undertake several exercises and readings. First, we'll read and discuss Keith Ratzlaff's ekphrastic poetry collection, Dubious Angels. I've proposed a series of questions below that might help us into the book. First, though, you might want to know more about the writer and his approach to poetry, generally, and ekphrasis in particular. This multimedia interview from a few years back, including many mp3s of the poet reading from his poems, could offer much fuel for discussion about the poems and about the processes that lead to poems.

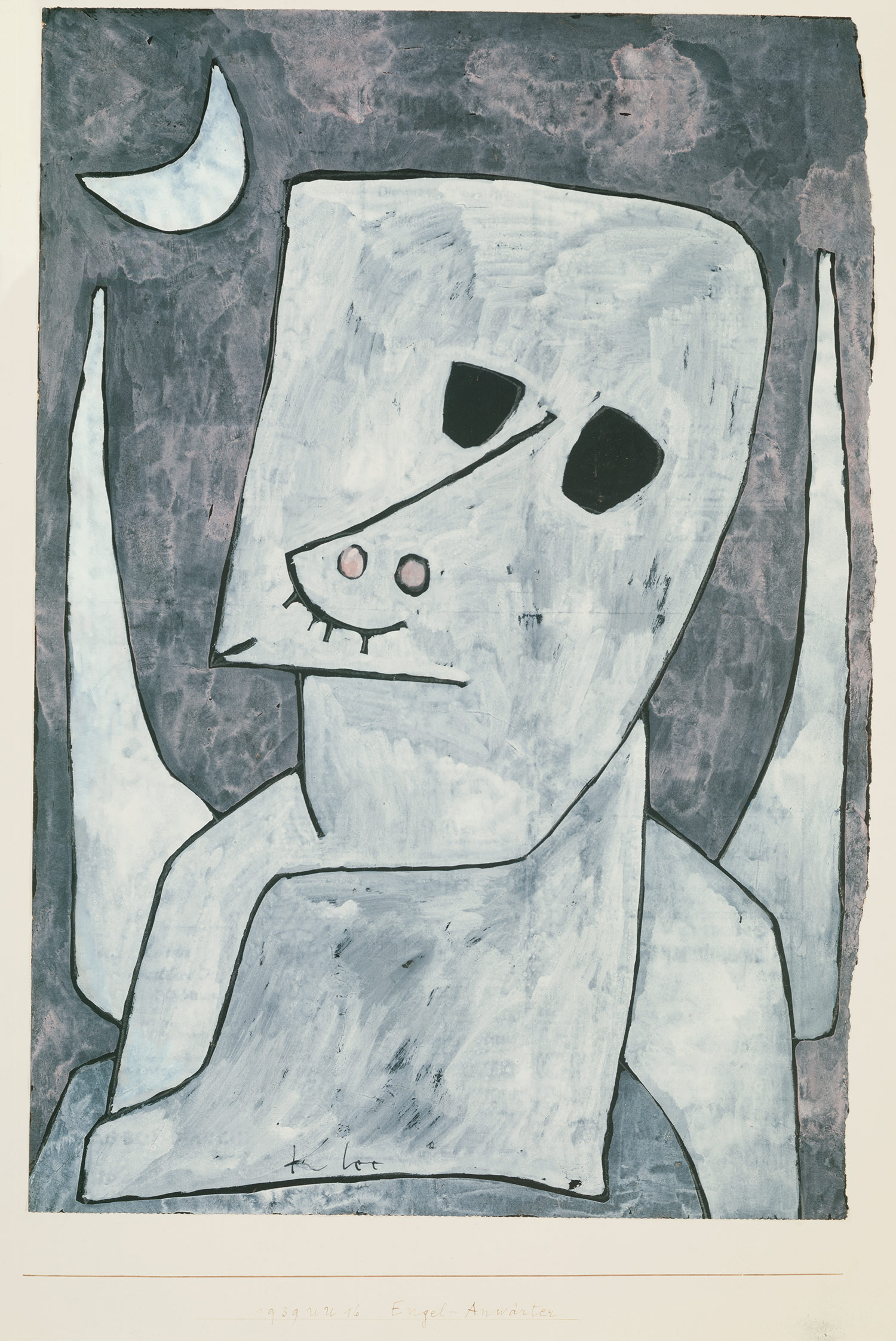

Second, you'll want to familiarize yourself a bit with Paul Klee and his work. The Klee Museum in Bern is a rich resource, including not only images but wonderful articles. (As it turns out, by poking around here I learned a great deal about Klee's interest in music.) A full, translated text of Klee's diaries

used to be available online, but I have not been able to find it recently.

used to be available online, but I have not been able to find it recently. Each poem in Ratzlaff's collection responds to an image of an angel created by Klee, mostly engravings made near the end of his life. Read Ratzlaff's preface, where he concludes, "I don't mean for the poems to speak for Paul Klee, nor have I wanted to turn the drawings into illustrations for the poems, or to make poems that are passive ekphrastic exercises."

Instead, the poet pitches his attempt as approximating Klee's "tragicomic voice and his jazz-like technique" as a way to give "the angels voices that do justice to the bodies Paul Klee created for them." Consider these questions as a way into the poems (and as a way of discovering means of your own for making similar poetic attempts).

1) Which angel poems seem mostly to be verbal transcripts of the images? What liberties does R. seem comfortable with in these pieces? What fidelities does he seem compelled to keep?

2) Which poems take the most fantastic leaps from the images? What fragments of the original do they retain? What vehicles carry the poems away (narratives, voices, forms)?

3) Note the uses Ratlzlaff makes of Klee's own writings (esp. in "Precocious Angel"). What do they do to the poem's voice and texture? Can you tell where the painter's voice starts and where the poet's takes over? How does this matter or not to you? How do masks work in such poems?

4) What use do you make of the notes? Should they be there? Why or why not? How do you think of the notes in relation to this quotation from Ratzlaff:

But no poet I know writes to make meaning, at least not initially. I write to make things, to control the world in some modest way. One thing many of my beginning literature students seem to believe is that poets are intentionally obscure. When students are really paranoid, they seem to believe poets mean for them personally to feel stupid. But that confuses the reader's problems with the writer's. I don't know any poet who is willfully obscure. When I'm in the act of writing a poem--and during that first ur-reading writers do--I'm convinced there's only one meaning for the poem and that the meaning is clear. Content isn't the issue, style is. Thus Klee's emphasis--always in the Sketchbook--is on the how. Criticism and theory, interpretive acts that rightfully belong to the reader, come later, hopefully traveling along at least some of the paths the work has cut out for it. When it works right, the poet and reader walk the path together.

5) How do you make sense of the collection's title, "Dubious Angels?" Read carefully the poem "Doubting Angel" on p. 63, which includes the lines: "Raising my hand / in the air as blessing / only requires / that I believe in air." What kinds of belief do the poems require of us? What kinds of belief do you require of your readers?

Addition

The note to "Last Earthly Step" refers to Walter Benjamin's discussion of Klee's "Angelus Novus." Here's that image and Benjamin's quotation:

“A Klee painting named ‘Angelus Novus’ shows an angel looking as though he is about to move away from something he is fixedly contemplating. His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one perceives the angel of history. His face is towards the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.”

Walter Benjamin Theses on the Philosophy of History

2 comments:

I propose that we make it mandatory that all poets must record themselves reading their poetry and post it online in easy to find places. For those long dead, we must devise a plan to ressurect them. For those who do not speak English, we must set them on the course to learn, that they may translate and read aloud their poems for us. Either that, or we must invest our time in producing flaming tongues above our heads to make all speech recognizable.

~

I particularly enjoyed Athlete's Head by Ratzlaff.

Blade--Consider it so decreed.

dw

Post a Comment