Taking pride in original songwriting however begs the question, What is an original song, when it comes to folk music (or any genre)?

All aspects of creativity are basically reconstituted bits and pieces of things we’ve seen, heard and experienced, finely or not-so-finely chopped and served in a form that hopefully blends the ingredients into something “new.” The ancient Greeks seemed to know this, expressed in their belief that the Muses of creativity were the daughters of Mnemosyne, Titan goddess of memory. Perhaps we would like to think that the thoughts that go into creating a new song are purely impressions from “real life,” but a melody does not suggest itself as much from the impression of the 6 train ride you took this morning as it does from a melody from another song. The same for chord progressions, song concepts, lyric sounds and patterns, song structures and everything else. Folk music is supposed to be a shared continuum after all, and as Louie Armstrong said, “All music is folk music, I ain’t never heard no horse sing a song.”

Despite knowing all this, as a supposedly “creative” artist I am often shocked to discover that a song I’ve written has been a blatant unconscious rip-off of somebody else’s song, either in its structure, or lyrics, etc; if I’m lucky the other person’s song is not particularly popular or recognizable!

from a column by singer/songwriter/thief Jeffrey Lewis. Here's his Had it all on Youtube.

Showing posts with label poetics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label poetics. Show all posts

Sunday, August 10, 2008

Wednesday, August 6, 2008

Ars poetica

It has been made a question, whether good poetry be derived from nature or from art. For my part, I can neither conceive what study can do without a rich [natural] vein, nor what rude genius can avail of itself: so much does the one require the assistance of the other, and so amicably do they conspire [to produce the same effect].

from Horace, Epistles, Book II, Ars Poetica

from Horace, Epistles, Book II, Ars Poetica

Monday, August 4, 2008

Entering the work

Mennonite poet (and friend) Jean Janzen has a wonderful memoir/essay interspersed with poems published in the Spring 2008 issue of Mennonite Life. What I like about the poem below, among many things, is the way she weaves her mother's presence into a Titian altarpiece she sees in Venice. In the painting, she sees "the image of my mother in a studio family photograph in which she holds her first daughter in her lap. Here she was in a city threatened by floods, like her ancestry, 'alive' and glowing." Somehow, though, the poem doesn't make the painting just a Rorschach of her past, but sets up a real exchange, a dialogue with the painter and the viewer. Here's the poem:

My Mother in Venice

She had another life,

not only the vast expanse

of prairie, but this island

adrift and shimmering.

Here she is, in the Frari Church

holding the Child.

Centuries ago Bellini

saw her at the fish market

shivering in the rain,

brought her to the small

fire of his studio

and began brushing her round

face into glow, dressing her in blue silk-my mother

in this city of mirrors

where the centuries swirl

together, where she still holds

the Child, my Brother, where she doesn't hold me.

My Mother in Venice

She had another life,

not only the vast expanse

of prairie, but this island

adrift and shimmering.

Here she is, in the Frari Church

holding the Child.

Centuries ago Bellini

saw her at the fish market

shivering in the rain,

brought her to the small

fire of his studio

and began brushing her round

face into glow, dressing her in blue silk-my mother

in this city of mirrors

where the centuries swirl

together, where she still holds

the Child, my Brother, where she doesn't hold me.

Thursday, July 3, 2008

Real Sofistikashun

Probably one of the funniest two or three poets writing in English, Tony Hoagland is also one of the more humane, thoughtful, and helpful writers of work on how to write and read contemporary verse. His collection of essays Real Sofistikashun has a wonderful opening piece on Image, Diction and Rhetoric that I am likely to include in a future course packet. Other useful essays from the collection can be found on line.

Fragment, Juxtaposition, And Completeness: Some Notes And Preferences

How to Talk Mean and Influence People or here

Fear of Narrative and the Skittery Poem of Our Moment

Three Tenors: Glück, Hass, Pinsky, and the Deployment of Talent or here

One of my favorites is on the dilemma of Self-Consciousnes. Hoagland writes of the initial loss of innocence that comes with studying writing:

The gradual intrusion of self-consciousness is one inevitable side effect of an education in art. To read ten poems, or a hundred, is one thing. To read ten thousand is another. As we internalize more of the tradition and become progressively less shielded by our ignorance, we realize how local our upbringing has been, how much there might be to know, and perhaps even, sigh, how limited our talent. T.S. Eliot’s Prufrock comes to know that he is not Prince Hamlet; we must deal with the fact that we are not Eliot. When a person takes the step toward learning more of craft and its history, more of artifice—when, for example, a person crosses the threshold of an MFA program—she chooses to end a childhood in artlessness. She gives up some of their innocent infatuation, the naïveté, the adolescent grandiosity, maybe even some of the natural grace of the beginner. “They are good poets because they don’t know yet how hard it is to write a poem,” I have heard a teacher say, a bit tartly, of her beginning poetry class.

Yet, he goes on to point out, that is part of the necessity of poetic growth:

Self-consciousness in writing, as it does in life, open up a kind of delay between impulse and action, between thought and word. That pause—as these examples show—offers the opportunity for calculated intensifications and angularities that would never occur in “natural,” uninformed speech.

And he concludes with this helpful notion about intelligence, cleverness, and the reader:

Self-consciousness often provokes an overexertion of cleverness. But intelligence, when used well in a poem, never makes the reader feel less smart than the writer, or left behind. Rather, it gives the reader the exhilarating pleasure of being smart in concert with the speaker. . . . To learn what a poet needs to know is to become an initiate; that initiation imposes burdens as well as powers. We have the obligation to make real poems, to contribute to the living, evolving heritage of poetry. . . . Finally, if our awareness of the great Past makes us self-consciously anxious, it is good to remember that Everything has not been done. Possibility has not been exhausted. More reality is being made at the reality factory every day, and new ways to handle it are being invented—language is a technology, after all. Its adaptations are legion; its evolution is hardly over.

In the spirit of this blog, here's an excerpt from his poem Requests for Toy Piano:

Play the one about the family of the ducks

where the ducks go down to the river

and one of them thinks the water will be cold

but then they jump in anyway

and like it and splash around.

No, I must play the one

about the nervous man from Palestine in row 14

with a brown bag in his lap

in which a gun is hidden in a sandwich.

Play the one about the handsome man and woman

standing on the steps of her apartment

and how the darkness and her perfume and the beating of their hearts

conjoin to make them feel

like leaping from the edge of chance—

Friday, June 27, 2008

The longer tradition

from Viz: Rhetoric-Visual Culture-Pedagogy

One conversation about the relationship between the visual and the textual concerns ekphrasis, commonly defined as the poetic description of a work of art. Regretfully, this popular definition of the term disregards the long and rich rhetorical tradition of ekphrasis, which has been understood as the rhetorically charged description of anything that can be perceived visually or evoked mentally.

Although there are plenty of examples of ekphrasis in classical literature, the earliest extant instructions on how to compose one and what its functions are appear in the Hellenistic composition handbooks known as progymnasmata . . . . These handbooks were designed to train young people in public speaking, and they taught that an ekphrasis was not meant to be composed for its own sake, but it should rather be a part of a longer oration. In this context, the ekphrasis served to evoke a vivid picture in the mind of the audience so as to sway its members’ emotions and prepare them for the subsequent analytical and/or narrative exposition of the issue at hand. An ekphrasis could be composed in any style; it could be used as an introduction (proemium), substituted in the place of a narrative, or inserted as a pointed digression. When inscribed around an image, such as an icon, the ekphrasis functioned to provide commentary and/or guide the viewer’s interpretation of the patron’s intent. Occasionally—and this is especially true for the late antique and Byzantine period—an entire oration could be comprised of an ekphrasis, which functioned allegorically to illustrate either vice or virtue, creation or destruction, wisdom or folly, temperance or intemperance—but always with a rhetorical goal, embedded in a specific historical context.

One conversation about the relationship between the visual and the textual concerns ekphrasis, commonly defined as the poetic description of a work of art. Regretfully, this popular definition of the term disregards the long and rich rhetorical tradition of ekphrasis, which has been understood as the rhetorically charged description of anything that can be perceived visually or evoked mentally.

Although there are plenty of examples of ekphrasis in classical literature, the earliest extant instructions on how to compose one and what its functions are appear in the Hellenistic composition handbooks known as progymnasmata . . . . These handbooks were designed to train young people in public speaking, and they taught that an ekphrasis was not meant to be composed for its own sake, but it should rather be a part of a longer oration. In this context, the ekphrasis served to evoke a vivid picture in the mind of the audience so as to sway its members’ emotions and prepare them for the subsequent analytical and/or narrative exposition of the issue at hand. An ekphrasis could be composed in any style; it could be used as an introduction (proemium), substituted in the place of a narrative, or inserted as a pointed digression. When inscribed around an image, such as an icon, the ekphrasis functioned to provide commentary and/or guide the viewer’s interpretation of the patron’s intent. Occasionally—and this is especially true for the late antique and Byzantine period—an entire oration could be comprised of an ekphrasis, which functioned allegorically to illustrate either vice or virtue, creation or destruction, wisdom or folly, temperance or intemperance—but always with a rhetorical goal, embedded in a specific historical context.

Tuesday, June 3, 2008

Focus on the dogs, cats, and pet birds

An excerpt from poet Alfred Corn’s Notes on Ekphrasis, a solid overview of the practice:

Actually, a poem about an obscure painting is also at a disadvantage. Where the original image is well known, we can compare it to the poet's version of what it contains; and the poet's departures from the original, or inaccurate interpretations of it, are sometimes revealing. Without the original image, though, we are forced to trust the poet's description as being accurate, and we are unable to know where it is not. Meanwhile, the compositional task is much more difficult in such cases since the text of the poem has to convey all the relevant visual information, while still qualifying as poetry. On the other hand, if the subject is, say, Leonardo's Mona Lisa, or any other very famous work of art, there's no need to give a detailed description; the audience already knows what's in the painting.

A disadvantage, though, of using very great works of visual art as a subject for ekphrasis is that the comparison between the original and the poem about it may prove too unfavorable. Readers may wonder why they should bother reading a moderately effective poem when they could instead look at the great painting it was based on. If the poem doesn't contain something more than was already available to the audience, it will strike the reader as superfluous, the secondary product of someone too dependent on the earlier, greater work.

The reader may also wonder why the description wasn't done in prose rather than in lines of poetry. All art historians and critics agree that complete and accurate verbal descriptions of visual art are very hard to achieve, even in prose. When the expectations associated with good poetry are part of the goal as well, we see that writing a good ekphrastic poem is a formidable task indeed. The aim of drafting a text entirely adequate to its source, giving a verbal equivalent to every detail in the subject work, is probably too lofty. A more realistic goal is to give a partial account of the work.

Once the ambition of producing a complete and accurate description is put aside, a poem can provide new aspects for a work of visual art. It can provide a special angle of approach not usually brought to bear on the original. For example, in a banqueting scene, the poem might, instead of describing the revelers, focus on the dogs, cats, and pet birds given free rein in the scene.

Actually, a poem about an obscure painting is also at a disadvantage. Where the original image is well known, we can compare it to the poet's version of what it contains; and the poet's departures from the original, or inaccurate interpretations of it, are sometimes revealing. Without the original image, though, we are forced to trust the poet's description as being accurate, and we are unable to know where it is not. Meanwhile, the compositional task is much more difficult in such cases since the text of the poem has to convey all the relevant visual information, while still qualifying as poetry. On the other hand, if the subject is, say, Leonardo's Mona Lisa, or any other very famous work of art, there's no need to give a detailed description; the audience already knows what's in the painting.

A disadvantage, though, of using very great works of visual art as a subject for ekphrasis is that the comparison between the original and the poem about it may prove too unfavorable. Readers may wonder why they should bother reading a moderately effective poem when they could instead look at the great painting it was based on. If the poem doesn't contain something more than was already available to the audience, it will strike the reader as superfluous, the secondary product of someone too dependent on the earlier, greater work.

The reader may also wonder why the description wasn't done in prose rather than in lines of poetry. All art historians and critics agree that complete and accurate verbal descriptions of visual art are very hard to achieve, even in prose. When the expectations associated with good poetry are part of the goal as well, we see that writing a good ekphrastic poem is a formidable task indeed. The aim of drafting a text entirely adequate to its source, giving a verbal equivalent to every detail in the subject work, is probably too lofty. A more realistic goal is to give a partial account of the work.

Once the ambition of producing a complete and accurate description is put aside, a poem can provide new aspects for a work of visual art. It can provide a special angle of approach not usually brought to bear on the original. For example, in a banqueting scene, the poem might, instead of describing the revelers, focus on the dogs, cats, and pet birds given free rein in the scene.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

“Ekphrasis is about physical as much as verbal translation, about moving the visual object from its original residence into the house of words and then restoring and revivifying it” –Grant F. Scott, from The Sculpted Word: Keats, Ekphrasis and the Visual Arts (University Press of New England, 1994).

Tuesday, May 13, 2008

Ekphrasis and Discovery

Leonard Barkan on ekphrasis in his Unearthing the Past: Archaeology and Aesthetics in the Making of Renaissance Culture . Here's a little taste of his discussion, how ekphrasis follows discovery:

In the face of these new interrelations, Sangallo and the other onlookers respond in two ways: they draw and they talk. They create more works of art, and they conduct an impromptu seminar on the history of art. The words are a sign that art has a history that deserves to stand alongside the history of power or of nature, while the establishment of a past history of art directs the course of art's future history. The images are a sign that art can be made not only out of dogma, out of natural observation, or out of historical events, but also out of art itself. The words and images together produce aesthetics—which is to say a philosophy and a phenomenology proper to art itself. The unearthed object becomes the place of exchange not only between words and pictures but also between antiquity and modern times and between one artist and another.

A piece of marble is being rediscovered, but at the same time a fabric of texts about art is being restitched. Writings from later antiquity—Ovidian poetry, Roman novels, Greek romances, lyrics, and rhetorical exercises—turn out to be filled with passages, typically what are called ekphrases, in which narrative is framed not as reality but as the contents of an artist's picture. These passages stand in ambiguous relation to the actual objects emerging from the ground. Ekphrases are categorically different from the works of art they supposedly describe; indeed, the poetic description of an imaginary sculpted Laocoön would doubtless not resemble the statue in Rome any more than Virgil's narrative does. Yet this fabric of texts tantalizes readers with the possibility that, together with the rediscovered works themselves, it will reconstruct a complete visual antiquity. In addition, the ekphrastic literature brings with it a set of ways to look at the visual arts and a set of relations between aesthetic representation and language.

In the face of these new interrelations, Sangallo and the other onlookers respond in two ways: they draw and they talk. They create more works of art, and they conduct an impromptu seminar on the history of art. The words are a sign that art has a history that deserves to stand alongside the history of power or of nature, while the establishment of a past history of art directs the course of art's future history. The images are a sign that art can be made not only out of dogma, out of natural observation, or out of historical events, but also out of art itself. The words and images together produce aesthetics—which is to say a philosophy and a phenomenology proper to art itself. The unearthed object becomes the place of exchange not only between words and pictures but also between antiquity and modern times and between one artist and another.

A piece of marble is being rediscovered, but at the same time a fabric of texts about art is being restitched. Writings from later antiquity—Ovidian poetry, Roman novels, Greek romances, lyrics, and rhetorical exercises—turn out to be filled with passages, typically what are called ekphrases, in which narrative is framed not as reality but as the contents of an artist's picture. These passages stand in ambiguous relation to the actual objects emerging from the ground. Ekphrases are categorically different from the works of art they supposedly describe; indeed, the poetic description of an imaginary sculpted Laocoön would doubtless not resemble the statue in Rome any more than Virgil's narrative does. Yet this fabric of texts tantalizes readers with the possibility that, together with the rediscovered works themselves, it will reconstruct a complete visual antiquity. In addition, the ekphrastic literature brings with it a set of ways to look at the visual arts and a set of relations between aesthetic representation and language.

Friday, April 11, 2008

Ah, an essay for next fall's course

Debra Allbery's fine essay on ekphrasis at the Cortland Review. I like this little bit:

I've been interested particularly in this notion suggested by Stevens and Hollander—that our problems are the same; that we turn to painting not only for inspiration, but instruction.

That is true for me, both in writing about the visual and in writing about music.

Thanks to Therese L. Broderick for the excellent tip.

dw

I've been interested particularly in this notion suggested by Stevens and Hollander—that our problems are the same; that we turn to painting not only for inspiration, but instruction.

That is true for me, both in writing about the visual and in writing about music.

Thanks to Therese L. Broderick for the excellent tip.

dw

Friday, March 28, 2008

Trainer poems

Kay Ryan calls ekphrastic poems "trainer poems" here (scroll down a bit):

I should start by admitting that I have a certain prejudice. I am inclined to see poems-about-paintings as easy poems, or exercises, or trainer poems. The writer is playing tennis against a nice, solid backboard. The artwork is already there; all the poet has to do is dance around in front of something both fixed and culturally valuable. One feels a sense of pre-approval if one writes about Great Art.

But then, later, after exploring some of her own ekphrastic impulses, Ryan writes:

But enough complaining. An artist I’ve returned to over and over in poems is not a painter but the French composer, Eric Satie. In contrast to the thoroughly not-Cassatt poem above, the Satie poem that follows IS, I think, very Satie—and ekphrastic—even though it’s a pure fabrication. Because I’m going to define an ekphrastic poem as one that invokes the spirit of the artist (without having to describe features of any actual work.) Call me a cheater.

"Invoking the spirit of the artist"--how does that strike as a definition of ekphrasis?

I should start by admitting that I have a certain prejudice. I am inclined to see poems-about-paintings as easy poems, or exercises, or trainer poems. The writer is playing tennis against a nice, solid backboard. The artwork is already there; all the poet has to do is dance around in front of something both fixed and culturally valuable. One feels a sense of pre-approval if one writes about Great Art.

But then, later, after exploring some of her own ekphrastic impulses, Ryan writes:

But enough complaining. An artist I’ve returned to over and over in poems is not a painter but the French composer, Eric Satie. In contrast to the thoroughly not-Cassatt poem above, the Satie poem that follows IS, I think, very Satie—and ekphrastic—even though it’s a pure fabrication. Because I’m going to define an ekphrastic poem as one that invokes the spirit of the artist (without having to describe features of any actual work.) Call me a cheater.

"Invoking the spirit of the artist"--how does that strike as a definition of ekphrasis?

Saturday, February 23, 2008

Uncle Walt and American Song

An excerpt from this essay by Whitman scholar David S. Reynolds, author of Walt Whitman's America:

Recalling the entertainment experiences of his young manhood, Whitman wrote, "Perhaps my dearest amusement reminiscences are those musical ones." Music was such a powerful force on him that he saw himself less as a poet than as a singer or bard. "My younger life," he recalled in old age, "was so saturated with the emotions, raptures, up- lifts of such musical experiences that it would be surprising indeed if all my future work had not been colored by them."

Whitman regarded music as a prime agent for unity and uplift in a nation whose tendencies to fragmentation and political corruption he saw clearly. For all the downward tendencies he perceived in society, he took confidence in Americans' shared love of music. In the 1855 preface to Leaves of Grass he mentioned specifically "their delight in music, the sure symptoms of manly tenderness and native elegance of soul." As he explained in a magazine article: "A taste for music, when widely distributed among a people, is one of the surest indications of their moral purity, amiability, and refinement. It promotes sociality, represses the grosser manifestations of the passions, and substitutes in their place all that is beautiful and artistic." By becoming himself a "bard" singing poetic "songs" he hoped to tap the potential for aesthetic appreciation he saw in Americans' positive responses to their shared musical culture.

Whitman's poetry, then, was most profoundly influenced by what he called "the great, overwhelming, touching human voice—its throbbing, flowing, pulsating qualities." Of the 206 musical words in his poems, 123 relate specifically to vocal music, and some are used many times. "Song" appears 154 times, "sing" 117, and "singing" and "singers" over 30 times each. In his poems, too, he mentions no fewer than 25 musical instruments, including the violin, the piano, the oboe, and the drums. One senses a musical influence in his poem "Song of Myself," which, like a symphony, shifts between pianissimo passages and torrential, fervent ones.

Friday, February 22, 2008

Second Naivete--Hearing Again

"[I]n every way, something has been lost, irremediably lost: immediacy of belief. But if we can no longer live the great symbolisms of the sacred in accordance with the original belief in them, we can, we modern men, aim at a second naivete in and through criticism. In short it is by interpreting that we hear again. . . . [T]he second immediacy that we seek and the second naivete that we await are no longer accessible to us anywhere else than in a hermeneutics; we can only believe by interpreting" (352-354).

"[I]n every way, something has been lost, irremediably lost: immediacy of belief. But if we can no longer live the great symbolisms of the sacred in accordance with the original belief in them, we can, we modern men, aim at a second naivete in and through criticism. In short it is by interpreting that we hear again. . . . [T]he second immediacy that we seek and the second naivete that we await are no longer accessible to us anywhere else than in a hermeneutics; we can only believe by interpreting" (352-354).--Paul Ricouer, from The Symbolism of Evil

Wednesday, February 13, 2008

Heidegger, meet Billy Collins

Thanks to my friend and colleague Jay Wood for pointing out this piece by Adam Kirsch from a recent edition of Poetry:

Ours does not promise to go down in literary history as a great age of religious poetry. Yet if contemporary poetry is not often religious, it is still intensely, covertly metaphysical. Human nature, it seems, compels us to keep asking about the first things, even if we no longer accept the same answers that our ancestors did, or even the same kind of answers. The more widely you read, in fact, the clearer it becomes that our poetry has a distinctive metaphysics, a set of principles or intuitions held in common by poets as different as Seamus Heaney, Charles Simic, and Billy Collins. This metaphysical sensibility, I think, is what will give our period a retrospective unity, when readers of the future come to survey what looks to us like chaos. And the best document of that sensibility—the single piece of writing that does the most to explain what our poetry believes, and the ways it expresses that belief—is an essay by Martin Heidegger, "The Origin of the Work of Art."

Labels:

Adam Kirsch,

Billy Collins,

Charles Simic,

Heidegger,

poetics,

Seamus Heaney

Monday, November 12, 2007

Basic Poetic(s) Question(s)--The Visual Ear

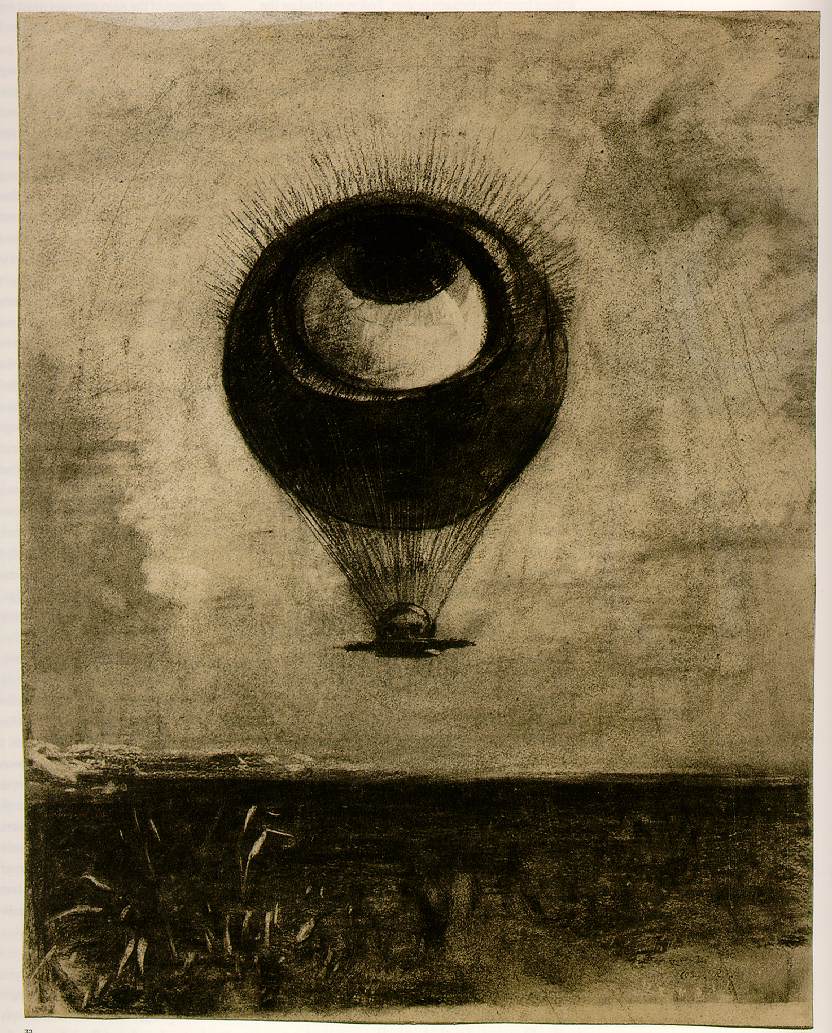

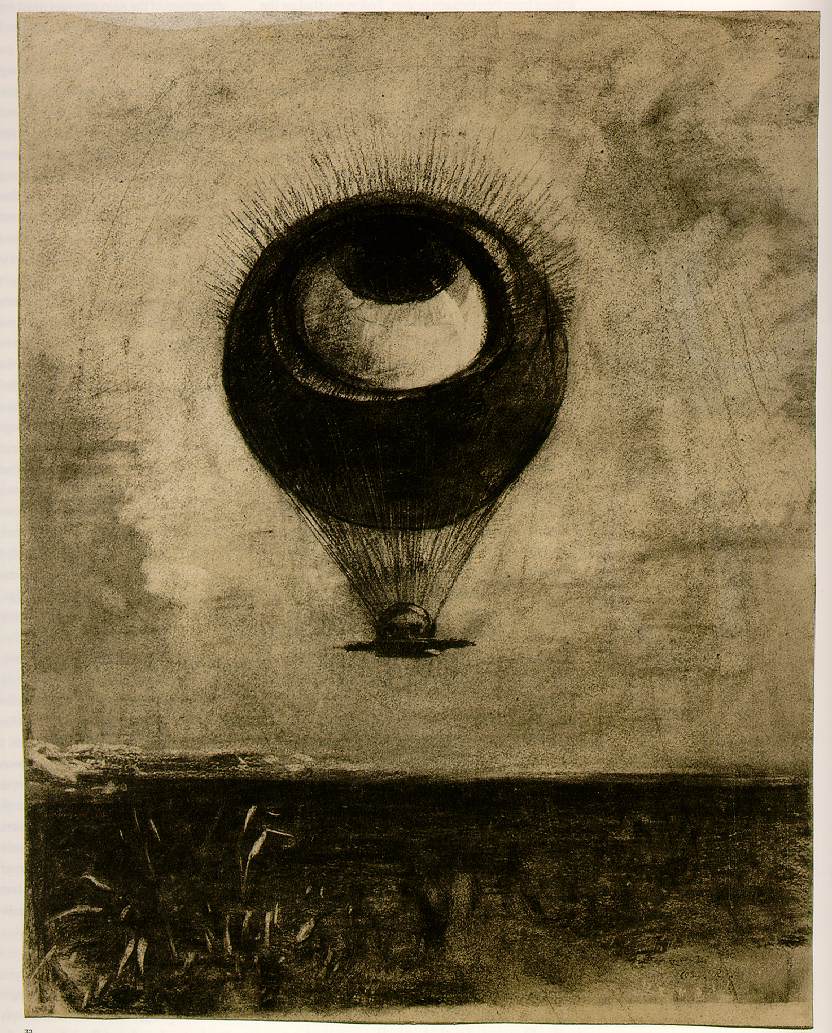

In a review of Mary Jo Bang's The Eye Like a Strange Balloon, Donna Stonecipher raises the/a key poetic(s) question for ekphrastic poetry: "Must I know the work of art to “get” the poem? How much am I missing if I don’t know it?" In other terms, can/does the poem stand on its own and does that matter. Stonecipher rightly describes ekphrasis as "a wonderfully elastic process" and suggests that "Only an art fiend (and Bang herself) would know all the artworks in question, but Bang is so meticulous that this fact doesn’t detract from the pleasures of the poems. Reading her work is such an intensely visual experience, in fact, that trying to keep one picture in mind while being presented with picture after picture in the poems would be pretty much impossible. "

So the spinning and confusion and pleasures of visual discovery in language make the poems, at least for Stonecipher. She

traces the means of discovery in Bang's work and concludes "that the poems proceed as much by sound as by sight. One uses one’s 'visual ear' to read her poems. Puns and double entendres turn into images. Images cede themselves to sonic grandeur. It is this high-stakes game of the visual and the aural, and their interplay as in a whirling two-butterfly mating dance, that give Bang’s poems their particular charge."

Here's the book's title poem, based on a piece by Odilon Redon.

The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity--Mary Jo Bang

We were going toward nothing

all along. Honing the acoustics,

heralding the instant

shifts, horizontal to vertical, particle

to plexus, morning to late,

lunch to later yet, instant to over. Done

to overdone. And all against

a pet store cacophony, the roof withstanding

its heavy snow load. So, winter. And still,

ambition to otherwise and a forest of wishes.

Meager the music floating over.

The car in the driveway. In the P-lot, or curbside.

A building overlooking an estuary,

inspired by a lighthouse.

Always asking, Has this this been built?

Or is it all process?

Molecular coherence, a dramatic canopy,

cafeteria din, audacious design. Or humble.

Saying, We ask only to be compared to the ant-

erior cruciate ligament. So simple. So elegant.

Animated detail, data from digital.

But of course there is also longstanding evil.

The spider speaking

to the fly, Come in, come in.

Overcoming timidity. Overlooking consequence.

Finally ending

with the future. Take comfort.

You were going nowhere. You were not alone.

You were one

of a body curled on a beach. Near sleep

on a balcony. The negative night in a small town or part

of an urban abstraction.

Looking up

at the billboard hummingbird,

its enormous beak. There’s a song that goes . . .

And then the curtain drops.

Odilon Redon, The Eye Like a Strange Balloon

Mounts Toward Infinity, charcoal on paper, 1882

So the spinning and confusion and pleasures of visual discovery in language make the poems, at least for Stonecipher. She

traces the means of discovery in Bang's work and concludes "that the poems proceed as much by sound as by sight. One uses one’s 'visual ear' to read her poems. Puns and double entendres turn into images. Images cede themselves to sonic grandeur. It is this high-stakes game of the visual and the aural, and their interplay as in a whirling two-butterfly mating dance, that give Bang’s poems their particular charge."

Here's the book's title poem, based on a piece by Odilon Redon.

The Eye Like a Strange Balloon Mounts Toward Infinity--Mary Jo Bang

We were going toward nothing

all along. Honing the acoustics,

heralding the instant

shifts, horizontal to vertical, particle

to plexus, morning to late,

lunch to later yet, instant to over. Done

to overdone. And all against

a pet store cacophony, the roof withstanding

its heavy snow load. So, winter. And still,

ambition to otherwise and a forest of wishes.

Meager the music floating over.

The car in the driveway. In the P-lot, or curbside.

A building overlooking an estuary,

inspired by a lighthouse.

Always asking, Has this this been built?

Or is it all process?

Molecular coherence, a dramatic canopy,

cafeteria din, audacious design. Or humble.

Saying, We ask only to be compared to the ant-

erior cruciate ligament. So simple. So elegant.

Animated detail, data from digital.

But of course there is also longstanding evil.

The spider speaking

to the fly, Come in, come in.

Overcoming timidity. Overlooking consequence.

Finally ending

with the future. Take comfort.

You were going nowhere. You were not alone.

You were one

of a body curled on a beach. Near sleep

on a balcony. The negative night in a small town or part

of an urban abstraction.

Looking up

at the billboard hummingbird,

its enormous beak. There’s a song that goes . . .

And then the curtain drops.

Odilon Redon, The Eye Like a Strange Balloon

Mounts Toward Infinity, charcoal on paper, 1882

Friday, November 2, 2007

HOW TO READ, AND PERHAPS ENJOY, VERY NEW POETRY

This article by Stephen Burt in The Believer is finally on line. I like this quotation:

The most important precepts are the simplest: look for a persona and a world, not for an argument or a plot. Enjoy double meanings: don’t feel you must choose between them. Ask what the disparate elements have in common—do they stand for one another, or for the same thing? Are they opposites, irreconcilable alternatives? Or do they fit together to represent a world? Look for self-descriptive or for frame-breaking moments, when the poem stops to tell you what it describes. (Classic Ashbery poems tend to end with these: “I will keep to myself. / I will not repeat others’ comments about me.”; “A randomness, a darkness of one’s own.”) Use your own frustration, or the poem’s apparent obliquity, as a tool: many of these poems include attacks on assumptions or pretenses that make ordinary conversational language, and newspaper prose, so smooth.

A couple of years ago, I got to interview Stephen for Avatar Review. He is very smart.I asked him a little bit about ekphrasis and he said:

At Yale in the 1990s, it seemed that everyone got attracted to ekphrasis—John Hollander had just written a book on the subject and taught classes on it. When I was writing some of those poems I was surrounded by poets and critics who took a strong interest in how poets could represent paintings (and sculpture and architecture and other visual arts).

I started writing poems about paintings before that, though—I wrote the Velazquez poem when I lived in Oxford. I like paintings. Paintings with character and narrative components—and you can find those components in apparently abstract artists, if you look; I often find them in Franz Kline—give poets a chance to sort-of make up, and sort-of discover, all sorts of stories and scenes. Ekphrases also let you flip back and forth between talking about a work of art as an object (and about the situation of its making), on the one hand, and talking about what the work depicts on the other—between, if I can use the terms here, diegetic and extradiegetic perspectives. I like poems (and critics) who can do those kinds of flips.

Friday, October 19, 2007

More Poetics

"A poem is like a human face — it is at the same time an object that can be measured, catalogued, described, and also an appeal. You may hear an appeal or ignore it, but it's difficult simply to limit yourself to checking it with a tape measure."

--Adam Zagajewski

--Adam Zagajewski

Friday, September 28, 2007

A Redundant Riff on Tension in Poetry

Originally posted at The Gazebo, an online poetry workshop.

1) The tension between sentence and line is, for me, what makes poetry poetic. The play between these two basic units of meaning not only tugs between one meaning and another, but also can stretch out sound, rhythm and meter. Enjambment, obviously, is a key way to make this tension work. In A Poet’�s Guide to Poetry, Mary Kinzie talks about it this way: �”When the line ends before the sentence does, we can say that the threshold of the line is in tension with that of the sentence. In cases of such tension, the line can provide a partial or temporary meaning or suggestion that is at odds with the meaning of the completed sentence. I call these provisional meanings before moving off the line half-meanings. The half meanings of the lines that run on would be in tension with the whole meaning that emerges when the sentence has come to its end”� (49).

One of the best examples of this that I know is in Scott Cairns'� poem �The Spiteful Jesus.� Cairns writes about the particularly American version of a savior who was:

borne to us in the little boat

that first cracked rock at Plymouth

petty, plainly man-inflected

demi-god established as a club

with which our paling

generations might be beaten

to a bland consistency.

The play on the half-meaning of the word �club� is absolutely dependent on the sentence-line tension, as a reader’�s temporal experience of the poem changes, completely, how you read the word after finishing the whole sentence.

2) The second kind of tension I think about is also in the above section by Cairns, and that�s the pull between several connotations or allusions attached to a single term or image. "�Borne to us"� does this, as does "�club"� and "�paling."� It'�s more than just punning, I think. It�’s the simultaneous opening up and shutting down of possible meanings that creates a tension for the reader, a mostly good tension, though too much of it can wear me down when I read.

3) The last kind of tension, and one I�’m less good at using in my own writing, is to play with and against a reader�'s metrical expectations. Obviously a caesura does this. So can a slight change in the accentual quality of a particular metrical pattern. Robert Frost’�s �Home Burial� uses these kinds of tensions to heighten the narrative tension that already exists between the spouses. The poem has what one critic calls a �subverbal menace which gets it about right in my book. To accomplish that, Frost fiddles with the elements of blank verse, inserting daunting pauses that emphasize the gap between the man and woman and also using colloquial speech in ways that break up the natural iambic pentameter. This little bit comes from the beginning of the poem:

She took a doubtful step and then undid it

To raise herself and look again. He spoke

Advancing toward her: 'What is it you see

From up there always -- for I want to know.'

She turned and sank upon her skirts at that,

And her face changed from terrified to dull.

He said to gain time: 'What is it you see?'

In the second, third and last lines here, the caesuras really stop the movement of the line and sharpen the narrative tension. And the same can be said for his repeated phrase, which doesn�’t precisely scan.

1) The tension between sentence and line is, for me, what makes poetry poetic. The play between these two basic units of meaning not only tugs between one meaning and another, but also can stretch out sound, rhythm and meter. Enjambment, obviously, is a key way to make this tension work. In A Poet’�s Guide to Poetry, Mary Kinzie talks about it this way: �”When the line ends before the sentence does, we can say that the threshold of the line is in tension with that of the sentence. In cases of such tension, the line can provide a partial or temporary meaning or suggestion that is at odds with the meaning of the completed sentence. I call these provisional meanings before moving off the line half-meanings. The half meanings of the lines that run on would be in tension with the whole meaning that emerges when the sentence has come to its end”� (49).

One of the best examples of this that I know is in Scott Cairns'� poem �The Spiteful Jesus.� Cairns writes about the particularly American version of a savior who was:

borne to us in the little boat

that first cracked rock at Plymouth

petty, plainly man-inflected

demi-god established as a club

with which our paling

generations might be beaten

to a bland consistency.

The play on the half-meaning of the word �club� is absolutely dependent on the sentence-line tension, as a reader’�s temporal experience of the poem changes, completely, how you read the word after finishing the whole sentence.

2) The second kind of tension I think about is also in the above section by Cairns, and that�s the pull between several connotations or allusions attached to a single term or image. "�Borne to us"� does this, as does "�club"� and "�paling."� It'�s more than just punning, I think. It�’s the simultaneous opening up and shutting down of possible meanings that creates a tension for the reader, a mostly good tension, though too much of it can wear me down when I read.

3) The last kind of tension, and one I�’m less good at using in my own writing, is to play with and against a reader�'s metrical expectations. Obviously a caesura does this. So can a slight change in the accentual quality of a particular metrical pattern. Robert Frost’�s �Home Burial� uses these kinds of tensions to heighten the narrative tension that already exists between the spouses. The poem has what one critic calls a �subverbal menace which gets it about right in my book. To accomplish that, Frost fiddles with the elements of blank verse, inserting daunting pauses that emphasize the gap between the man and woman and also using colloquial speech in ways that break up the natural iambic pentameter. This little bit comes from the beginning of the poem:

She took a doubtful step and then undid it

To raise herself and look again. He spoke

Advancing toward her: 'What is it you see

From up there always -- for I want to know.'

She turned and sank upon her skirts at that,

And her face changed from terrified to dull.

He said to gain time: 'What is it you see?'

In the second, third and last lines here, the caesuras really stop the movement of the line and sharpen the narrative tension. And the same can be said for his repeated phrase, which doesn�’t precisely scan.

Labels:

craft,

poetic line,

poetics,

Robert Frost,

Scott Cairns

A Primer on the Poetic LIne

Why lines matter in poetry

The line is, for most readers, what makes a poem something other than what we read and speak in the rest of our lives. Like prose or conversation, poems are made of discrete terms, sentences and phrases (and fragments, and noises). What seems to distinguish the poem from these other instantiations of language is lineation and its effects on meaning, sound, and movement. Of course this is simplistic—heightened attention to diction, to “formed” language, to figures of speech, to image, to sensory encounters with both idea and emotion—these also comprise the territory of a poem. But they do not do so as exclusively as the line. Line breaks, line lengths, lines arranged in stanzas, and “memorable lines” collect to give us visual, auditory, and meaningful encounters with poetry. What follows is a primer on the poetic line, a stripped down but useful list of some of the factors and choices that contribute to poetic lineation as it has developed and is practiced by contemporary poets writing in English. (Please see the bibliography below and interlaced links, both indicating my sources for these notes).

Two (usually supplemental not contradictory) ways to view a poetic line

1) As a metrical or sonic measure of language—as primarily a device that controls and moves a reader’s experience across and through the auditory landscape of a poem. In metrical verse (verse that measures and repeats), patterns of emphasis on stressed and unstressed syllables create the movement or stopping of a poem. In rhymed verse, the ends of lines coincide with particular word sounds. In free verse, line breaks and enjambment alternate between movement and rest, giving emphasis and attention to particular words or combination of sounds. In Whitman’s poems, echoing the parallelism of the Psalms and prophets, repeated beginnings and structures of sentences--anaphora--produces a definitive cadence. In some free verse, poets consider the line to be a unit of breath. See Levertov on this.

2) As a unit of meaning that works in distinction from or cooperation with a poem’s other grammatical elements, primarily the sentence. Lines that enjamb, for instance, can create half-meanings that are extended or challenged by the subsequent line. Mary Kinzie argues that it is “partial meaning and dissatisfaction” the compel us to keep reading in a poem, that propel us forward. Champions of the organic line insist that a poem’s lines should mimic the subjects they represent, or the experience of those subjects (think of Whitman’s or Ginsberg’s long lines). Others will suggest that each line of a poem should have a kind of independence and weight that merits being set off as a line. Kinzie, again, suggests that the very act of creating lines indicates the substance of each line is equal to that of another—this is a measure of meaning rather than merely of sound.

Ten reasons to end a poetic line

1) Formal/Metrical reasons often determine where to stop. Whether writing iambic pentameter, common meter hymns or pop tunes, a line often needs to end once a certain collection of stresses and syllables has been collected.

2) Lines often close at the ends of phrases or sentences. In Hebrew poetry, for instance, the opening or closing tags determine a line’s shape (see Ps. 70:2-4, for instance). Other parallelisms—antithetical ones, for example—can also make this determination.

3) Free verse tends to offer two kinds of lineation—broken phrases (anti-grammatical) and more complete units of phrase (grammatical). These can both be end-stopped or enjambed to varying effect.

4) Many poets enjoy employing violent or dramatic line-breaks that draw attention to themselves, to particular terms, sounds or meanings. See G. Brooks’ We real cool. Other line breaks are more subtle, drawing less attention to themselves. Both sorts seem necessary for one another.

5) Lines end when they carry a certain weight of image or meaning, when that vision or sense matches the weight and shape of other lines. This goes to Kinzie’s idea about lineation itself suggesting a measure of equality between lines.

6) Lines work to create provisional meanings, to foreshadow a sentence’s conclusion or to set up a tension between the line’s meaning and that of the sentence or phrase once it is complete. See Scott Cairns’ The Spiteful Jesus. A warning here—the continuous use of tension can lead in time to no tension at all.

7) Repetition (and variation) of a phrase, set of sounds, or metical unit can determine line length or ending. Anaphora is one example of this sort of lineation.

8) Rhymes and slant rhymes can be reasons for ending a line. Rhyme often affects enjambment by couching or curbing it—giving range to the movement of a sentence. However, enjambment tugs against rhyme because line tugs against sentence. End stopped rhyme offers a formal set of sonic stop to the poem while enjambment moves the poem forward, the rhyme being a kind of passing connectivity but not a stoppage.

9) Grammatical or syntactic inversion can also be reasons to shape and end a particular line. The variance on the Subject-Verb-Object construction creates its own set of contingent meanings and connotations (mention parataxis v. hypotaxis, or Cairns’ appositives in a poem like Possible Answers to Prayer).

10) The imagistic, sonic, symbolic or cognitive stress of ending and beginning words also matter in breaking a line. For this reason, many poets take care that the ending word of a line is significant in one or more of these ways. An opening up of connotation (or a more denotative shutting down) might be especially important to consider at the end of a line. Some poets think of a strong word (strong in any on of several senses—meaning, sound, image--being the landing point, or turning point, for a line’s ending.

What some poets say about the line, the sentence, and the poem

Jorie Graham on long lines:

When you’re using many sentence-length lines, what becomes useful is parsing out key stresses at turning points—where the line breaks, and where it resumes. Deciding which terms are going to be in stressed positions, how each one is going to “back up,” as it were, all preceding stress points, makes for a very relativistic prosody, but one that can be precise in spite of the length of the phrasings. . . the trick is to get the right words stressed of necessity by a reader in order to key the emotion down the page.

Graham on the shorter line:

Once you being talking from the position of being a social creature, you go back to the line in which social discourse takes place, the pentameter. It’s a more exterior line, which, since Shakespeare, we associate with people speaking to one another. On either side of it stand more unspeakable lines—longer lines for the visionary; shorter and more symmetrical ones for song, spell, hymn; and shorter yet for the barely utterable, the shriek, the epitaph.

Graham, again, on the indented line:

The indented line became a very useful place to negotiate and control the music of the poem. I was . . . very interested in the sentence, in the kinds of energies the sentence awakens—desire for closure, desire for suspension of closure, desire for simultaneity in a stream of temporal action that defies simultaneity. . . . what happens along the way of the sentence that you’re in the process of undertaking, the think you can’t put alongside but that has to actually happen in the sentence as a “dependent” phrase?

The indented line allows you to modulate the sentence and keep it capable of carrying so much without collapsing. It’s all a matter of freight carried to speed of carriage, to mangle Frost’s quote. It gave me a kind of lift—and three musical units: the full line, the shorter fragmentary line that condenses stresses on very few words—often words that could never carry a stress—prepositions, articles, conjunction—words which, if stressed, truly alter the nature of actual inquiry of the poem is; and the “landing”—the often-times single word on the left margin which takes the strongest stress of all. Those “landing words” gave me a king of propulsion that made a rather long poem feel like a containable lyric utterance.

Charles Wright on the work of a line, short or long

“Each line should be a station of the cross."

Mark Doty from Souls on Ice (describing the writing process of the poem “A Display of Mackerel”).

I did feel early on that the poem seemed to want to be a short-lined one, I liked breaking the movement of these extended sentences over the clipped line, and the spotlight-bright focus the short line puts on individual terms felt right. "Iridescent, watery," for instance, pleased me as a line-unit, as did this stanza:

prismatics: think abalone,

the wildly rainbowed

mirror of a soapbubble sphere,

Short lines underline sonic textures, heightening tension. The short a's of prismatics and abalone ring more firmly, as do the o's of abalone, rainbowed and soapbubble. The rhyme of mirror and sphere at beginning and end of line engages me, and I'm also pleased by the way in which these short lines slow the poem down, parceling it out as it were to the reader, with the frequent pauses introduced by the stanza breaks between tercets adding lots of white space, a meditative pacing.

Michael Ryan, from Grammar for Poets

One could also graph the sentences in poems across the same stylistic range, according to how they fulfill-frustrate-play with-or-against our S-V-O expectation. Poems no less than prose are made of sentences, and expectations of sentences (by the reader), and avoidances of sentences (by the writer). But they are also made of lines that alter our experience of sentences, by foregrounding the sounds of the words, phrases, and pauses which make up sentences but which we don't attend to until these sounds are highly organized and orchestrated. The primary instrument of this orchestration is the lines, and lines can also be arranged in stanzas, which may further foreground the lines by signifying their own organization independent of the sentences. The difference between metered and unmetered lines, in the strictest stanza forms to the free-est verse, is no more than the difference between the degree of foregrounding of the lines against the sentences, and therefore the degree to which our attention to those sentences is complicated.

Martin Heidegger, “Poetically, Man Dwells” from (Poetry, Language, Thought 221)

"Poetry is a measuring."

Adrian Blevins from In Praise of the Sentence

The sound of actual speech broken up into lines is not the same thing as poetry, for all good poetry must be contained or shaped in such a way as to alarm us into apprehending more than one meaning at a time. If Coleridge is right and “poetry reveals itself in the balance or reconciliation of opposite or discordant qualities,” conversational tones alone in a poem will sound too mundane or boring—too much like unformed Laundromat chatter—to move us. For this reason, speech effects are often countered and even contradicted by language used in more overly poetic ways. . . . Since linguists say that almost all sentences, both written and spoken, have never existed before, the way we put them together might be one of the only ways we have of distinguishing ourselves from others. The ways in which a poet sounds like nobody but himself is, again, in essence, what we call his voice. So perhaps it is possible to measure a poet’s worth by measuring his willingness to spend his fearlessness, which is just another way of saying all his energy, on the verbal manifestation of his peculiarity. Ironically, hearing the sound of peculiarity—of what many poets and critics call “the genuine” or “authentic”—might be the only way we have of really knowing that we are not alone. For to hear what sounds like a real person in the world speaking to you from the page (and even more startlingly, from beyond the grave) is to diminish the lonesomeness that we are born, witless and garbled and slippery and ignorant, to somehow bear.

Scott Cairns on the line, complexity and provisional meanings.

The line in poetry is one way that a poem opens up to complexity, one way it resists being simply a document of record, or a simple reference to a prior event. I usually talk about this strategy in terms of “parallel codes”: the syntactic and the stichic, respectively. Most English poems avail themselves of a fairly recognizable English syntax, even if they may not employ standard mechanical conventions. And the meaning generated by this recognizable syntax might be correctly apprehended as the primary sense of the utterance. All I’m saying for now is that . . . an English poem can generate an initial, a primary sense, an appreciable meaning. Even so, in a poem that employs the line—that is, in a verse poem—this overall sense delivered by syntax is intermittently interrupted by its being broken into stichs . . . broken into lines. Most devoted readers learn to be very attentive to these units, and are therefore about to witness, line by line (and at a finer level, word by word), a provisional sense which the line itself articulates, a momentary syntax that operates relatively independently of the larger syntax of the entire sentence. Very often, individual lines and/or variously apprehended groupings of lines can serve to suggest provisional meanings which can complicate, or even contradict, the sense delivered by the overall syntax.

Some things worth reading (some of which are the sources for these notes)

Addonizio, Kim and Dorianne Laux. The Poet's Companion. New York: Norton, 1997.

Dunne, Gregory. “A Conversation with Scott Cairns.” Prairie Schooner 79.1 (Spring 2005): 44-52.

Graham, Jorie. “The Art of Poetry,” The Paris Review 165 (Spring 2003): 52-97.

Kinzie. Mary. A Poet’s Guide to Poetry. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1999.

Levertov, Denise. "On the Function of the Line." New and Selected Essays. New York: New Directions, 1992.

Oliver, Mary. Rules for the Dance: A Handbook for Writing and Reading Metrical Verse. Boston: Houghton, 1998

The Line: Excerpts from Claims to Poetry

A Poetic Glossary and a Dictionary of Poetic Forms and Techniques from the Academy of American Poets.

Vince Gotera has a useful, more succinct discussionof line.

The line is, for most readers, what makes a poem something other than what we read and speak in the rest of our lives. Like prose or conversation, poems are made of discrete terms, sentences and phrases (and fragments, and noises). What seems to distinguish the poem from these other instantiations of language is lineation and its effects on meaning, sound, and movement. Of course this is simplistic—heightened attention to diction, to “formed” language, to figures of speech, to image, to sensory encounters with both idea and emotion—these also comprise the territory of a poem. But they do not do so as exclusively as the line. Line breaks, line lengths, lines arranged in stanzas, and “memorable lines” collect to give us visual, auditory, and meaningful encounters with poetry. What follows is a primer on the poetic line, a stripped down but useful list of some of the factors and choices that contribute to poetic lineation as it has developed and is practiced by contemporary poets writing in English. (Please see the bibliography below and interlaced links, both indicating my sources for these notes).

Two (usually supplemental not contradictory) ways to view a poetic line

1) As a metrical or sonic measure of language—as primarily a device that controls and moves a reader’s experience across and through the auditory landscape of a poem. In metrical verse (verse that measures and repeats), patterns of emphasis on stressed and unstressed syllables create the movement or stopping of a poem. In rhymed verse, the ends of lines coincide with particular word sounds. In free verse, line breaks and enjambment alternate between movement and rest, giving emphasis and attention to particular words or combination of sounds. In Whitman’s poems, echoing the parallelism of the Psalms and prophets, repeated beginnings and structures of sentences--anaphora--produces a definitive cadence. In some free verse, poets consider the line to be a unit of breath. See Levertov on this.

2) As a unit of meaning that works in distinction from or cooperation with a poem’s other grammatical elements, primarily the sentence. Lines that enjamb, for instance, can create half-meanings that are extended or challenged by the subsequent line. Mary Kinzie argues that it is “partial meaning and dissatisfaction” the compel us to keep reading in a poem, that propel us forward. Champions of the organic line insist that a poem’s lines should mimic the subjects they represent, or the experience of those subjects (think of Whitman’s or Ginsberg’s long lines). Others will suggest that each line of a poem should have a kind of independence and weight that merits being set off as a line. Kinzie, again, suggests that the very act of creating lines indicates the substance of each line is equal to that of another—this is a measure of meaning rather than merely of sound.

Ten reasons to end a poetic line

1) Formal/Metrical reasons often determine where to stop. Whether writing iambic pentameter, common meter hymns or pop tunes, a line often needs to end once a certain collection of stresses and syllables has been collected.

2) Lines often close at the ends of phrases or sentences. In Hebrew poetry, for instance, the opening or closing tags determine a line’s shape (see Ps. 70:2-4, for instance). Other parallelisms—antithetical ones, for example—can also make this determination.

3) Free verse tends to offer two kinds of lineation—broken phrases (anti-grammatical) and more complete units of phrase (grammatical). These can both be end-stopped or enjambed to varying effect.

4) Many poets enjoy employing violent or dramatic line-breaks that draw attention to themselves, to particular terms, sounds or meanings. See G. Brooks’ We real cool. Other line breaks are more subtle, drawing less attention to themselves. Both sorts seem necessary for one another.

5) Lines end when they carry a certain weight of image or meaning, when that vision or sense matches the weight and shape of other lines. This goes to Kinzie’s idea about lineation itself suggesting a measure of equality between lines.

6) Lines work to create provisional meanings, to foreshadow a sentence’s conclusion or to set up a tension between the line’s meaning and that of the sentence or phrase once it is complete. See Scott Cairns’ The Spiteful Jesus. A warning here—the continuous use of tension can lead in time to no tension at all.

7) Repetition (and variation) of a phrase, set of sounds, or metical unit can determine line length or ending. Anaphora is one example of this sort of lineation.

8) Rhymes and slant rhymes can be reasons for ending a line. Rhyme often affects enjambment by couching or curbing it—giving range to the movement of a sentence. However, enjambment tugs against rhyme because line tugs against sentence. End stopped rhyme offers a formal set of sonic stop to the poem while enjambment moves the poem forward, the rhyme being a kind of passing connectivity but not a stoppage.

9) Grammatical or syntactic inversion can also be reasons to shape and end a particular line. The variance on the Subject-Verb-Object construction creates its own set of contingent meanings and connotations (mention parataxis v. hypotaxis, or Cairns’ appositives in a poem like Possible Answers to Prayer).

10) The imagistic, sonic, symbolic or cognitive stress of ending and beginning words also matter in breaking a line. For this reason, many poets take care that the ending word of a line is significant in one or more of these ways. An opening up of connotation (or a more denotative shutting down) might be especially important to consider at the end of a line. Some poets think of a strong word (strong in any on of several senses—meaning, sound, image--being the landing point, or turning point, for a line’s ending.

What some poets say about the line, the sentence, and the poem

Jorie Graham on long lines:

When you’re using many sentence-length lines, what becomes useful is parsing out key stresses at turning points—where the line breaks, and where it resumes. Deciding which terms are going to be in stressed positions, how each one is going to “back up,” as it were, all preceding stress points, makes for a very relativistic prosody, but one that can be precise in spite of the length of the phrasings. . . the trick is to get the right words stressed of necessity by a reader in order to key the emotion down the page.

Graham on the shorter line:

Once you being talking from the position of being a social creature, you go back to the line in which social discourse takes place, the pentameter. It’s a more exterior line, which, since Shakespeare, we associate with people speaking to one another. On either side of it stand more unspeakable lines—longer lines for the visionary; shorter and more symmetrical ones for song, spell, hymn; and shorter yet for the barely utterable, the shriek, the epitaph.

Graham, again, on the indented line:

The indented line became a very useful place to negotiate and control the music of the poem. I was . . . very interested in the sentence, in the kinds of energies the sentence awakens—desire for closure, desire for suspension of closure, desire for simultaneity in a stream of temporal action that defies simultaneity. . . . what happens along the way of the sentence that you’re in the process of undertaking, the think you can’t put alongside but that has to actually happen in the sentence as a “dependent” phrase?

The indented line allows you to modulate the sentence and keep it capable of carrying so much without collapsing. It’s all a matter of freight carried to speed of carriage, to mangle Frost’s quote. It gave me a kind of lift—and three musical units: the full line, the shorter fragmentary line that condenses stresses on very few words—often words that could never carry a stress—prepositions, articles, conjunction—words which, if stressed, truly alter the nature of actual inquiry of the poem is; and the “landing”—the often-times single word on the left margin which takes the strongest stress of all. Those “landing words” gave me a king of propulsion that made a rather long poem feel like a containable lyric utterance.

Charles Wright on the work of a line, short or long

“Each line should be a station of the cross."

Mark Doty from Souls on Ice (describing the writing process of the poem “A Display of Mackerel”).

I did feel early on that the poem seemed to want to be a short-lined one, I liked breaking the movement of these extended sentences over the clipped line, and the spotlight-bright focus the short line puts on individual terms felt right. "Iridescent, watery," for instance, pleased me as a line-unit, as did this stanza:

prismatics: think abalone,

the wildly rainbowed

mirror of a soapbubble sphere,

Short lines underline sonic textures, heightening tension. The short a's of prismatics and abalone ring more firmly, as do the o's of abalone, rainbowed and soapbubble. The rhyme of mirror and sphere at beginning and end of line engages me, and I'm also pleased by the way in which these short lines slow the poem down, parceling it out as it were to the reader, with the frequent pauses introduced by the stanza breaks between tercets adding lots of white space, a meditative pacing.

Michael Ryan, from Grammar for Poets

One could also graph the sentences in poems across the same stylistic range, according to how they fulfill-frustrate-play with-or-against our S-V-O expectation. Poems no less than prose are made of sentences, and expectations of sentences (by the reader), and avoidances of sentences (by the writer). But they are also made of lines that alter our experience of sentences, by foregrounding the sounds of the words, phrases, and pauses which make up sentences but which we don't attend to until these sounds are highly organized and orchestrated. The primary instrument of this orchestration is the lines, and lines can also be arranged in stanzas, which may further foreground the lines by signifying their own organization independent of the sentences. The difference between metered and unmetered lines, in the strictest stanza forms to the free-est verse, is no more than the difference between the degree of foregrounding of the lines against the sentences, and therefore the degree to which our attention to those sentences is complicated.

Martin Heidegger, “Poetically, Man Dwells” from (Poetry, Language, Thought 221)

"Poetry is a measuring."

Adrian Blevins from In Praise of the Sentence

The sound of actual speech broken up into lines is not the same thing as poetry, for all good poetry must be contained or shaped in such a way as to alarm us into apprehending more than one meaning at a time. If Coleridge is right and “poetry reveals itself in the balance or reconciliation of opposite or discordant qualities,” conversational tones alone in a poem will sound too mundane or boring—too much like unformed Laundromat chatter—to move us. For this reason, speech effects are often countered and even contradicted by language used in more overly poetic ways. . . . Since linguists say that almost all sentences, both written and spoken, have never existed before, the way we put them together might be one of the only ways we have of distinguishing ourselves from others. The ways in which a poet sounds like nobody but himself is, again, in essence, what we call his voice. So perhaps it is possible to measure a poet’s worth by measuring his willingness to spend his fearlessness, which is just another way of saying all his energy, on the verbal manifestation of his peculiarity. Ironically, hearing the sound of peculiarity—of what many poets and critics call “the genuine” or “authentic”—might be the only way we have of really knowing that we are not alone. For to hear what sounds like a real person in the world speaking to you from the page (and even more startlingly, from beyond the grave) is to diminish the lonesomeness that we are born, witless and garbled and slippery and ignorant, to somehow bear.

Scott Cairns on the line, complexity and provisional meanings.

The line in poetry is one way that a poem opens up to complexity, one way it resists being simply a document of record, or a simple reference to a prior event. I usually talk about this strategy in terms of “parallel codes”: the syntactic and the stichic, respectively. Most English poems avail themselves of a fairly recognizable English syntax, even if they may not employ standard mechanical conventions. And the meaning generated by this recognizable syntax might be correctly apprehended as the primary sense of the utterance. All I’m saying for now is that . . . an English poem can generate an initial, a primary sense, an appreciable meaning. Even so, in a poem that employs the line—that is, in a verse poem—this overall sense delivered by syntax is intermittently interrupted by its being broken into stichs . . . broken into lines. Most devoted readers learn to be very attentive to these units, and are therefore about to witness, line by line (and at a finer level, word by word), a provisional sense which the line itself articulates, a momentary syntax that operates relatively independently of the larger syntax of the entire sentence. Very often, individual lines and/or variously apprehended groupings of lines can serve to suggest provisional meanings which can complicate, or even contradict, the sense delivered by the overall syntax.

Some things worth reading (some of which are the sources for these notes)

Addonizio, Kim and Dorianne Laux. The Poet's Companion. New York: Norton, 1997.

Dunne, Gregory. “A Conversation with Scott Cairns.” Prairie Schooner 79.1 (Spring 2005): 44-52.

Graham, Jorie. “The Art of Poetry,” The Paris Review 165 (Spring 2003): 52-97.

Kinzie. Mary. A Poet’s Guide to Poetry. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1999.

Levertov, Denise. "On the Function of the Line." New and Selected Essays. New York: New Directions, 1992.

Oliver, Mary. Rules for the Dance: A Handbook for Writing and Reading Metrical Verse. Boston: Houghton, 1998

The Line: Excerpts from Claims to Poetry

A Poetic Glossary and a Dictionary of Poetic Forms and Techniques from the Academy of American Poets.

Vince Gotera has a useful, more succinct discussionof line.

Wednesday, September 26, 2007

More from Christian Wiman

Over at sweatervestboy, I link to a handful of essays from Christian Wiman's new book, Ambition and Survival: Becoming a Poet.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)